In 1977 Alan Ayckbourn's Bedroom Farce was the first of his plays to be staged at the National Theatre. He was widely regarded at the time as a provider of middle brow, bitter-sweet comedies of middle-class lives and marriages such as How the Other Half Loves, The Norman Conquests and Absurd Person Singular, and had recently broken the record for having the most productions running simultaneously in the West End and on Broadway. "I was very pleased to be invited," he recalls, "but I do remember a lot of people saying to Peter Hall: 'What the hell is Mr Shaftesbury Avenue doing in the National?'"

Ten years later, at the high-water mark of radical Thatcherism, Hall asked Ayckbourn back to the National as both a writer and a director. The play he produced, A Small Family Business, which will be revived there next month, was not only a commercial success, but went on to be hailed by Mark Ravenhill as "one of the most intensely political plays of the period", and ranked by Michael Billington among the 10 best British plays of the 20th century for its "devastating assault" on the "entrepreneurial values we were taught to admire in the 80s".

So what had changed in the intervening decade? Actually, not very much. Ayckbourn's apparently light subject matter, on closer inspection, was not that light at all. The domestic comedies were full of real emotional pain and even violence that had been partially masked by his facility for comedy and theatrical ingenuity. "I don't think that I've ever been a political writer, but I think I've been a social writer," he says. "I am interested in the world around me although I generally write about the domestic, so it's more the Jane Austen model of managing to reflect her times without having too much on the Napoleonic wars."

Although Ayckbourn can see why A Small Family Business is described as an anti-Thatcherite play, he says "really most of my ideas grow from smaller and lower-level things. This came in part from watching my dear late mother, who in her later years worked in offices and would pocket things at the end of the day. I'm sure she wasn't the only one taking paper clips or a few pens, but I really thought it was a slippery slope and I fully expected her to come up the drive one day with a desk under her arm. I also had a wider sense of values being chipped away at by subclauses: thou shall not steal, except if it's not that big a thing; thou shall not kill, apart from … So I started on the story of a man, a good and honest man, who does something few of us would object to when he helps his daughter after she is nabbed for shoplifting a sachet of shampoo that costs peanuts."

Against the backdrop of a suburban family party, Ayckbourn's protagonist begins to pull at some small threads of corruption, "doing things we all might condone in themselves, until we find ourselves neck-deep in shit and asking how the hell we got here. People thought it somehow fitted with the mood of the 80s, but if anything that sort of resigned acceptance of things has got worse and it is rather sad that the play appears to be even more apposite now than it was then."

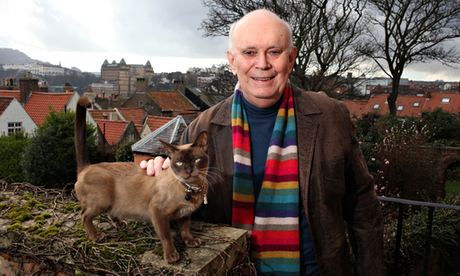

Ayckbourn, who is 75 in May, has written 78 plays, the majority of which have stayed in the repertory, provoking much inconclusive speculation as to whether he or Shakespeare is more performed in the UK in any given year. Although he suffered a stroke a few years ago and has problems with his hip, A Small Family Business is just one of three significant projects this year. As he puts it, "ever since I tried to retire a while back, things have got busier". In July, at the Stephen Joseph theatre in Scarborough, his base for nearly the entirety of his career, he will direct a revival of his 1998 musical, The Boy Who Fell into a Book. "Ever since Jeeves in the 70s [written with Andrew Lloyd Webber and a legendary flop] I have brought strong men to their knees with my involvement in musicals, so people have been warned." And in September, Scarborough will see the premiere of a new Ayckbourn play, Roundelay, for which he has again dipped into his bag of theatrical tricks in his career-long attempt to find new ways to tell a story.

The evening will be made up of five 20-minute plays "that are sort of related or share the same characters. I describe them as a chocolate box with some having soft centres and some very hard. I wanted to see whether changing the order made a difference to them and so, half an hour before the show opens, we'll get a member of the audience to pick some Ping-Pong balls out of a bag which will determine the running order and provoke a lot of loud ripping of Velcro in the dressing rooms."

Over the years other examples of Ayckbourn's structural inventiveness have included alternative scenes based on a coin toss (Sisterly Feelings); a trilogy of plays set at the same time but in different rooms (The Norman Conquests) and two plays sharing actors and running concurrently in the same theatre (House & Garden). "When I started in theatre in the 50s we were essentially emulating what cinema could do so much better. Then television brought theatre into people's own homes with production values that poor old weekly rep could not keep up with. So I've always wanted the audience to experience something uniquely live that they couldn't get anywhere else. If you run a theatre year after year as I have done, you can see when audiences become lethargic, and so you need some bright object to wave in front of them. In a way they are sort of gimmicks, but more importantly they are a way of telling a story that also shouts 'Hey! We're actually here with you.'"

Ayckbourn was born in Hampstead in 1939 into a household he describes as "quite arty in that my mother was a writer when I was young, and my father a violinist who was also leader of the LSO, but I didn't really know him well because he and my mother separated when I was very young and I was brought up in a single-parent home." His mother, Lolly, was a highly successful writer of stories for women's magazines – "in the super-tax bracket at one point" – who provided Ayckbourn with both material and a model of the writing life.

"I would go with her up to Fleet Street to see editors. They soon forgot I was there, but as a seven-year-old I was an open recording machine and at the women's press club, in a room of super glossy female journalists, I got a lot of women's angles on things, including a very biased view of marriage from my mother's remarks about my father, who had left her for a younger violinist." Ayckbourn would later find out more details about his parents' relationship, including the fact that they were never married, as his mother was actually married to someone else.

Ayckbourn was sent to boarding school aged seven, but during the holidays would write himself, quickly discovering that he preferred dialogue to "the long descriptive bits". When he later "inherited" a younger stepbrother they would play toy soldiers together, "but pretty soon he would go off and I'd be left with these soldiers asking each other 'is your leg hurting a lot?' before beginning to question what they were going to do with the rest of their lives. So I've pretty much been writing plays since I could talk to myself."

At his secondary boarding school, Haileybury in Hertfordshire, his attraction to the theatre was nurtured by a teacher who had worked with the actor-manager Sir Donald Wolfit, and Ayckbourn found himself touring Europe and north America in schoolboy versions of Shakespeare before leaving school for a stage manager job in Wolfit's company. "He was the first real actor that I'd met and I thought that must have been normal," laughs Ayckbourn. "He was such an enormous character both on stage and off stage, and when he got close to you, as he often did, you would see these huge pores in his skin with spots of greasepaint still in there. It was a face that had always been on stage."

Over the next few years Ayckbourn's primary focus was acting and he worked at several regional theatres, including the Library Theatre, Scarborough, where he encountered the man who would become his mentor, Stephen Joseph, as well as theatre-in-the-round, an important starting point for many of his subsequent plays. When Joseph died, Ayckbourn took over the running of the theatre, a task he undertook for nearly 40 years until stepping down in 2009. As a young actor in Scarborough, Ayckbourn says he became increasingly annoyed about not being given the right parts. "Rather than being Frankenstein, I was always his friend who got bumped off halfway through. In the end I complained to Stephen, who said if I wanted better parts I should write them myself and asked for a play for the following summer, with the condition that I would also be in it."

The Square Cat opened in 1959, the same year as Ayckbourn the actor was directed by Harold Pinter in a production of The Birthday Party, and in which he married his first wife, Christine Roland. "It was a silly thing about a girl who fell in love with a pop star and went off with him to the horror of her family," he explains. "But whereas a lot of plays by young writers are gloomy things complaining how your mother wrecked your life, this did have the advantage of being a comedy."

Ayckbourn continued writing, acting and directing, at Scarborough and elsewhere, until one of his plays "rang a West End bell", although even after reaching Shaftesbury Avenue success didn't come immediately. His play Mr Whatnot, an homage to silent movies that had been a success in rep – "90 per cent mime with 10 percent dialogue, most of which was inaudible" – was so savaged by leading critic Bernard Levin that it made Ayckbourn ill. "It was an unmitigated disaster. But the object lesson I learned was that something charming and lovely worked out for a stage in Stoke-on-Trent, with a group of actors you know intimately, and had directed yourself, can all be lost in the opening of a West End show where it became horrendously twee and pretty."

After the debacle of Mr Whatnot, Ayckbourn was steered towards the BBC, where he directed 50 plays in his first year in what was in effect "a crash course in cutting the crap". When Joseph then approached him to write a new play for Scarborough, Ayckbourn told him he was now a director and had "given all that up. There were so many great one-off voices around: Pinter, Wesker, Osborne, and by then I'd already tried to write a Pinter play, and tried something experimental with Mr Whatnot. I was getting tired of having to shout so loudly to be heard. Stephen said he knew I wanted to create a distinctive new voice, but why didn't I try to write a well-made play. And when I'd learned what the rules were, I could start breaking them."

Relatively Speaking, featuring relationship shenanigans on the cusp of the swinging 60s, "turned out to be my pension. It's a safe vehicle that has survived and is always on somewhere. And that provided the launch pad for How the Other Half Loves, again in one sense a fairly well‑plotted play, but using unusual theatre techniques in superimposing two rooms on top of each other, a pure in-the-round conceit."

Although his plays are performed all over the world, Ayckbourn says Scarborough is where "everything is born and the first place I think of when I have a new idea" (A Small Family Business is a very rare example of a play being written for another theatre). "It allowed me to get my plays on and see them succeeding or falling flat in front of real audiences. The first time an audience doesn't laugh or cry where they were supposed to, you call them idiots. But when a second and third audience also misses it then you realise it might be something to do with the play."

After the success of Relatively Speaking, he began to enjoy the "convenient treadmill" of producing a show for each summer that soon enough led to his huge popularity of the 1970s and his reputation as a chronicler of middle England adultery and divorce. "I suppose I wrote about what I knew. When I plunged out of school, I had barely been in the same room as a woman and married the second girl I met. We had our first son when I was still in my teens, a second son arrived little bit later and then the marriage disintegrated. By the time I was 25 I had been through that mill. I sometimes think most of my characters come from me in that I was writing out of my life without really writing about me." But having vowed not to marry again, in 1997, he and Christine were finally divorced and he married Heather Stoney, who had acted in his work in the 60s and been his partner for close to 30 years. Both events came at the same time as his knighthood and, unusually, both women are entitled to call themselves Lady Ayckbourn.

The conveyor belt of plays travelling from Scarborough to the West End continued, although it has not been without its tensions with the occasional "unhappy heave-ho" when producers wanting star names to take the parts created by actors in Scarborough. But the money generated by his plays has also made a significant contribution to keeping the theatre going. "I've never been that keen on travel or other expensive habits – although I suppose I was driving an Aston Martin by the time I was 30 – but the best thing the money has brought is freedom. And I think I also had the wit to realise what I had here in Scarborough was not second-best because it was away from the centre of things, but it was the best for me: I could write and direct the plays I wanted to. Although it was also a hell of a responsibility in one way, because if the play dies, as one in eight did, there was no one to blame apart from yourself."

His enthusiasm and love for the subsidised theatre system is undimmed. "It is still the place where risks can be taken. When on Earth did the West End ever do a new play which hadn't been developed somewhere else – usually at the National or the Royal Court or the regions? Commercial managements just don't take that sort of risk. My West End producer used to say to me, 'We're in the giggle business, darling.' And I'd sort of agree with him, but while I'm all for giggles, I'd also hope that some of what we do would be remembered for a little bit more than just that."

• A Small Family Business is at the National Theatre from 1 April and will be broadcast to more than 500 cinemas in the UK on 12 June as part of NT Live. The Boy Who Fell into a Book and Roundelay are at the Stephen Joseph theatre, Scarborough, this summer.