So, after 10 long years, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam has reopened – and what a wondrous sight it must be. Rembrandt's The Night Watch is still in pride of place but now a whole new gallery has been devoted to his young life, too, with glass and silver by makers of his acquaintance, and a portrait of his friend Jan Lievens of Constantijn Huygens, patron of the arts – the better that visitors might get a sense of the world in which the master was working.

I long to visit, and no doubt you feel the same. In the meantime, though, or perhaps as a primer ahead of a trip, why not try the marvellous – the utterly fantastic – new graphic biography of Rembrandt by the Dutch cartoonist Typex (the pseudonym of Raymond Koot). Commissioned by the Rijksmuseum, Rembrandt is published in the UK by SelfMadeHero, and it's a great fit for them, slipping in neatly among their graphic lives of, among others, Kiki de Montparnasse, Hunter S Thompson and Johnny Cash.

Rembrandt was born in Leiden in 1606, and he led a rackety kind of life, mostly as a result of his own compulsive spending. His wife, Saskia, lost three children early on, and died herself in 1642, a year after she had their son, Titus. After this, Rembrandt fell first for his baby's nurse, Geertje Dircx, and then for a servant, Hendrickje Stoffels, at which point Geertje took him to court for breach of promise, on the grounds that he had promised to marry her. Rembrandt retaliated by accusing her of pawning some of Saskia's jewellery, and later got her sent to a house of correction. Afterwards, he and Hendrickje lived happily together, though he couldn't afford to marry her; Saskia's will dictated that his share of her family fortune would be lost if he were ever to remarry. In 1656 he was forced to apply for bankruptcy, and his collection of paintings were sold off for a pittance. The story goes that he was so hard up he even sold Saskia's grave. Nevertheless, he continued to shop, even trying to buy himself a Holbein, as you do. He died in 1669.

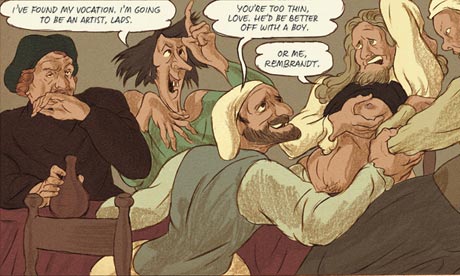

Typex covers all this ground, but episodically; like any good biographer, he understands that his subject's life turned on certain moments, and he has made these his focus. The atmosphere of the book is wonderful, Typex having captured both Rembrandt's vast appetites and the puritanism of the day – the one, you sense, endlessly feeding the other. The drawings are fantastic: they teem with life (and, sometimes, with rats). Typex, like Rembrandt, is good at faces, and the doughier the better; almost everyone in this book looks like a potato. It feels outrageous to write it but I think Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn would have adored this book. He would have admired its draughtsmanship and its wit and – given how many times he painted himself – he would have loved the fact that he is its star, warts and all.