Throughout the year 1913, Mussolini's favourite poet, Gabriele D'Annunzio, wrote the date "1912+1": he feared the unlucky number 13. In reality 1913 was an ambivalent year that looked forward to the carnage of the trenches, and back to a time before the old certainties died.

In his new book, 1913, Charles Emmerson chronicles the course of that pivotal year in 20 cities worldwide, among them Rome, London, Vienna, Istanbul and Buenos Aires. The result is a vast if bewilderingly disjointed panorama of social change and convulsion. By the end of the 1914-1918 conflict, more than 35 million people, both military and civilian, had been killed or wounded. The first world war was one of the deadliest conflicts in human history.

Emmerson, a historian at the Royal Institute of International Affairs, often loses sight of the broader picture. What links the cities thematically? Railways? Electric street lamps? On the whole, though, 1913 has narrative verve and insight. In lesser hands, a book that combines more than 500 pages of cultural history with pop sociology might easily stagnate.

After the unification of Italy in 1861, many viewed Rome as a sinkhole of papal corruption, swampy with the threat of malaria. Accordingly it was Turin – not Rome – which became the first capital of united Italy. The Piedmontese city's arcaded piazzas and geometric avenues were considered a "salubrious" alternative to Rome's dark backstreets. Rome did not become the Italian capital until 1871, 10 years after unification. Even, then, says Emmerson it was regarded by northern Europeans as a backward, ragamuffin city, whose dolce far niente – sweet languor – belied an obscure exuberance of life and Tangier-like decadence.

Berlin, by contrast, was in 1913 the forward-looking metropolis, with an electric tram network and eight times as many telephones per head as even London. The organisational virtues of the Prussian state were evident in Berlin's "spotless streets", says Emmerson, and the clockwork eating habits, with supper taken at precisely 8pm followed by a routine digestive.

In Buenos Aires the cultural life of 1913 was increasingly mindful of European proprieties and the high bourgeois traditions of Paris. With its tree-lined plazas and statues of frock-coated politicians, the Argentinian capital suggested a Paris of the pampas. In reality, says Emmerson, Buenos Aires was a vibrant immigrant hotchpotch and cultural pasticcio. The city's zoo itself was a hymn to cultural "diversity", with the aviary designed as a miniature Russian Orthodox church and the bear house a Jacobean castle.

The great cities of the world grew strong and rich by being open to foreigners. Vienna, capital of the Austro-Hungarian empire, united Serbo-Croats, Greeks, Bulgars and Transylvanians under the double-headed eagle of Emperor Franz Josef. The cosmopolitanism could not last, however. With a few deft strokes, Emmerson conjures an air of looming catastrophe in Vienna as Archduke Franz Ferdinand is about to be assassinated in Sarajevo in 1914 and the calamity attendant on the break-up of Habsburg crown lands breaks out. If the coming war dispersed and murdered people, the Austro-Hungarian empire had at least sheltered Jews and non-Jews alike in the multiethnic lands of Mitteleuropa. By the end of the conflict, from the eastern border of France all the way through Asia to the Sea of Japan, not a single pre-1913 government remained in power. The once mighty German, Habsburg, Russian and Ottoman empires had collapsed.

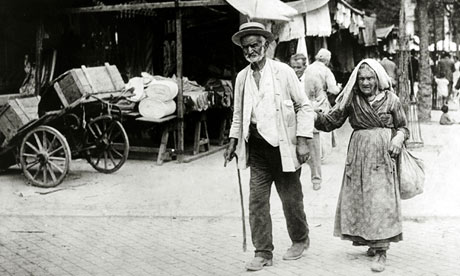

These days, "diversity" is a dubious word as politicians express their fear of a dysfunctional multiracial Europe. In Turkish north London, portraits of Atatürk – "The Father of the Turks" – stare out from grocer's shops and smoky men's clubs. After the break-up of the Ottoman empire, Atatürk ousted the hated Greeks from Istanbul and transformed the city into a westernised outpost supposedly free of Islam's influence. To judge by this book, however, Istanbul lost a good deal after the attempted erasure of Islam. Fabulous buildings built by pashas, viziers and other imperial mandarins were destroyed overnight, and the city was turned into a pale imitation of a western city, devoid of its 1913-era "kaleidoscopic variety".

London, in the author's estimation, was already in 1913 the "core of global finance", though not yet a city of conspicuous emotional spectacle. It would take the death of Princess Diana in 1997 and the state-funded funeral of Lady Thatcher to put paid to any pre-first world war values of the stiff upper lip. Ours is an age of lachrymose public display; it became so long after 1913, when the future was seen to frighten people like an unlucky number.

Ian Thomson's biography of Primo Levi is published by Vintage