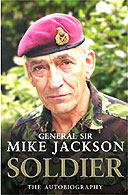

Soldier: The Autobiography

by General Sir Mike Jackson

400pp, Bantam, £18.99

This is a very readable, personal account by a man who rose to the top of the army and gained a reputation for being a "no-nonsense" commander. A towering figure, looked up to by the squaddies, Mike Jackson had his feet firmly on the ground. In perhaps the most dramatic episode of his career, recounted here with characteristic verve, he told Wesley Clark, Nato's supreme commander: "Sir, I'm not going to start world war three for you".

Jackson, head of Nato's ground forces in the Balkans during the 1999 Kosovo war, was told by Clark to prepare to block the runway at Pristina airport to prevent the Russians from coming. The Russians posed no threat, though they could have been dangerously provoked in the delicate situation because the Serbs, their traditional allies, were withdrawing the remnants of their army from Kosovo. It was not the first time Jackson considered resigning, though in the Pristina crisis he was fully supported by London.

Jackson makes his general view of the world quite plain via passing comments and sideswipes. Yet his book is curiously frustrating. We now know, he writes, that the intelligence about Saddam's weapons was "fool's gold". The release of the government's dossier, he says, "caused a stir in military circles". We want to know what they did about it.

Jackson attacks Donald Rumsfeld, US defence secretary at the time of the invasion of Iraq, describing him as "one of the most responsible for the current situation in Iraq". Yet he is an easy target; indeed, senior military figures at the time say they believe that with Blair, Bush, and others, he should be charged with war crimes under the Geneva Conventions for failing to fulfil their responsibilities as leaders of occupying powers. The military were further angered by the US decision in May 2003 to disband the Iraqi army and impose a "de-Baathification" policy. (Faced with criticism, both here and in the US, Paul Bremer, then head of the Coalition Provisional Authority in Baghdad, now insists the plan was approved by the White House and that British officials did not object at the time.)

Jackson says that all three heads of the armed forces expressed concern about Washington's failure to come up with a "post-conflict" plan. He claims that Admiral Sir Mike (now Lord) Boyce, then chief of the defence staff, passed on these concerns to both Blair and Geoff Hoon, his defence secretary. Revealingly, and worryingly, he adds: "though it may not have helped that [Boyce] didn't have an easy relationship with Hoon".

Jackson and Boyce argued that the Iraqi security forces should have been kept in place but put "under the command of the Coalition". Jackson simply comments: "To what extent the British Government communicated our concerns to the Americans I have no idea." In the end, the military chiefs, like the senior diplomats and intelligence and security officials opposed to the invasion, went along with whatever Blair wanted them to do.

"It was my constitutional duty not to express dissent in public for as long as I was in post," says Jackson. What did he say in public? He gives us a clue when he writes later in the book: "It would be unthinkable for the armed forces not to do as they are directed - or, worse, to act without authorisation. That is the road to anarchy." This, of course, raises the question of whether the military should do whatever they are directed to do, and under what circumstances they should resign.

The book raises another serious question. Jackson makes it clear that his enemies were not only on the battlefield. He had little time for the civil servants in the Ministry of Defence, or the Treasury. After railing against the state of army accommodation, he writes: "I did not find the MoD a comfortable place to be. Its values were not mine." Jackson blames the civil servants and ministers. One wonders whether he continued the fight or simply gave up the Whitehall battle.

Jackson also gives an account of Bloody Sunday, the day in January 1972 when soldiers from 1 Para fired on civil-rights marchers, resulting in 14 deaths. Jackson was then adjutant of the regiment. While he acknowledges he did not see any gunmen firing at the soldiers, he says there was "no doubt" in his mind that the Paras had come under fire. He makes a dig at the amount of time the Saville Inquiry into Bloody Sunday has taken to reach a conclusion and its expense. The controversy, he says, centres on the question of how British soldiers came to fire on "apparently unarmed civilians". It would be quite wrong, he argues, to attempt to answer the question until Lord Saville reports. But the Ministry of Defence admitted to the inquiry more than three years ago that none of those killed by the Paras were armed.

· Richard Norton-Taylor's Called to Account: The Indictment of Anthony Charles Lynton Blair ... is published by Oberon Books