It's 1913, and Angela Brazil's 10th boarding school story has just been published. By now, Brazil is well on her way to earning her later reputation as boarding school story grand dame. Her books, depicting all-female micro-societies controlled by teenage girls, have redefined the genre; for the first time in British fiction, their friendships, feelings, fears and frustrations take centre stage.

Unlike those in the fiction for young women that preceded Brazil's books – usually emphasising moral instruction and traditional gender roles – her characters are authentic and multi-dimensional. And with a focus on courage and independent spirit over physical appearance, class or other circumstantial factors, the books' true heroines are the ones bold enough to break the rules.

They sneak out at night, they take matters into their own hands; they're defiant, playful and irrepressible. And despite attempts to control them by archetypal authority figures such as parents and teachers, they never do as they're told. Today, their hijinks can be read as kitsch nostalgia; at the time the books were published, they were far more radical.

Beyond the pages of Brazil's books, the exciting possibilities they depicted remained distant. Although the suffrage movement was gaining momentum, access to education was inconsistent across the UK, especially for working class women, and there was widespread panic about the perceived decline in girls' morals. This is documented in detail in Carol Dyhouse's brilliant book Girl Trouble, which charts the media fascination and fear surrounding young women's progress towards equality throughout the last century (and echoed in Laurie Penny's latest, Cybersexism, which explores the way girls' online behaviour is controlled by a cultural paranoia of predators). Things were shifting, but slowly – and girls were definitely still discouraged from subversive "bad" behaviour.

Fast-forward a century, and girls are still the subject of endless ideological battles. Young women's thoughts, bodies and actions are controlled, pressured and policed at every turn, by a wider array of agendas and influences than ever before.

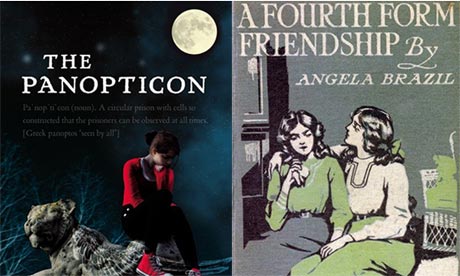

So maybe it's no wonder that the bad girl is back with a vengeance, giving contemporary fiction lovebites, bruises and a shoplifted bottle of super-strength cider to drink down the park. More than a century since Brazil's first book, and almost seven decades since Enid Blyton's first tale of Malory Towers, the fictional bad girl has gone to the dark side, getting into more extreme scrapes than ever before.

It's a natural evolution that's led from classroom mayhem to today's violent, sexual and at times even murderous teen antiheroines. Jenn Ashworth's Cold Light, for instance, is the chilling account of cruel, beautiful 14-year-old Chloe, found dead in a frozen lake with her much older, forbidden boyfriend in what seems like a Valentine's Day suicide pact – until another body is found nearby. Weirdo, by Cathi Unsworth, charts a private investigator's inquiries into the long-cold case of 15-year-old Corinne Woodrow, convicted amid media frenzy for murdering a classmate. And Anais Hendricks, the fierce, funny 15-year-old survivor who narrates Jenni Fagan's critically acclaimed debut The Panopticon, tells her tale from a detention centre for chronic young offenders, accused of putting a police officer in a coma after being found with matching blood on her school uniform.

The fictional bad girl is getting badder in the US, too – from the joyriding, activism and extortion of girl gang members in Joyce Carol Oates' Foxfire to the "young and out for glory" Sacred Heart Sluts in Colleen Curran's controversial Catholic schoolgirls novel Whores on the Hill, and the manipulative, malicious little madams in Gillian Flynn's Sharp Objects. (Flynn's world-conquering Gone Girl is about a rule-breaking adult, but the title itself has kicked off a whole publishing trend very much informed by what society expects and disapproves of in young women.)

Just as the rise of the now-classic boarding school story and its spunky, independent leading ladies corresponded to significant social and political changes further afield, such as the suffrage movement and educational reforms, so too today's bad girls mirror our wider cultural conflicts, issues, frustrations and fears.

It's tough being a teenage girl in the modern world, and – with on- and offline surveillance at an all-time high in real life and in fiction - the ones fighting the system provoke the most extreme emotions. Most bad girls are a combination of instigator and underdog, demanding recognition, respect, empathy and awe, and winning over readers with ease.

The best of this fictional breed are rebels with a cause, fighting for themselves and those they care about, against impossible odds. The bad girl represents the rebellious rule-breaker we all want to be, but with scars to show her fallibility and demonstrate the damage done to young women by today's society. Despite the bruises and broken hearts, her rebelliousness and resilience is intoxicating, and suggests she will endure for another century or more.

Have you got a favourite fictional bad girl? Which rebellious literary heroines would you want to raise hell with, and which ones deserve detention?