Charles Dickens is 200 years old this week (did you notice?). His reputation as a novelist is, of course, immense – and endlessly dissected at the moment. What fewer people know about is Dickens's obsession with drama. He was an avid theatregoer, joined the Garrick Club at the age of 25 and had many theatrical friends, including the actor William Macready to whom he dedicated Nicholas Nickleby. He visited circuses and melodrama houses; his periodical writings covered vents and "grimacers", waxworks, freak shows, actors, gaslight fairies and clowns. Rather than the highbrow literary figure that he is mainly seen as, shouldn't we claim him back as a man of the theatre, who captured in his writing all the scruff and scuzz of the London theatrical scene?

Dickens originally wanted to be an actor. In 1832, he lined up an audition for himself at Covent Garden, but a nasty head cold saw him miss this appointment with destiny, and it was a future of writing for him. His novels, though, are full of the theatre folk he met and observed: Nicholas Nickleby's jolly Vincent Crummles; the flirtatious Miss Snevellicci, who "always played some part in blue silk knee-smalls at her benefit", not to mention Ninetta, infant phenomenon at only 10 years old (for at least the last five years). Pip, in Great Expectations, sees a Hamlet of such dithering indecision that the audience weigh in to help him decide whether it is indeed nobler in the mind to suffer by holding a debate.

In his more hard-hitting journalism, Dickens depicted the jobbing actors hanging around the stage door, with their "indescribable public-house swagger": that fellow "in the faded brown coat and the very full light green trousers", another with "dirty white Berlin gloves", pretending to wealth and propriety while concealing poverty and a "two-pair back" in the New Cut. There are satirical characters too: the "theatrical young gentleman", with his pretensions to insider info: "here's a pretty to-do. Flimkins has thrown up his part in the melodrama at the Surrey!", and typical audience members at Astley's, including the very contemporary-sounding moody teenage son, desperately "trying to look as if he did not belong to the family".

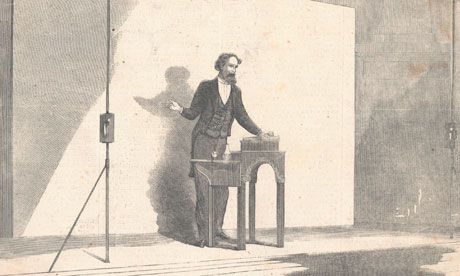

Even as a full-time novelist, Dickens never left performance entirely behind. Between 1853 and his farewell tour in 1870, he delighted, thrilled and unnerved audiences on both sides of the Atlantic with readings from his books. Thomas Carlyle, not always uncritical, commented in 1863 that he was "better than any Macready in the world; a whole tragic, comic, heroic theatre visible performing under one hat". He set his stage very carefully, with a dark-wine coloured reading stand and white kid gloves, and annotated his reading copies with stage directions: "snap your fingers", "shudder", "cupboard action" and the chilling "terror till the end!" With readings priced so that the ordinary working man and woman could attend, he worked through a repertoire of 16 extracts both comic and tragic: the courtroom scene from Pickwick Papers, the youthful romance of David Copperfield, the ever-popular Christmas Carol, and, most famously, his intense rendering of the murder of Nancy by Bill Sikes in Oliver Twist. This last was so ferocious and horrifying that in 1868 his friend and biographer John Forster begged him to stop, lest he kill himself with the effort.

Dickens warned his daughter Katey not to go on the stage, sagely noting that "although there are nice people on the stage, there are some who would make your hair stand on end". With his capacity for inducing theatrical thrills, he may well have been one of them. So, for this most notable of anniversaries, go on a Dickens walk, download a Dickens podcast, watch a TV adaptation – even pick up a book. But don't forget that first and foremost, Charles Dickens was a man of the theatre, who loved all the life and vitality of London's theatre scene, both on stage and off.