Foxes have been the baddies of children’s tales since the Ancient Greeks. This has made it easier to hunt and torment them – but how much of the myth is based in fact? What would the fox say if she told her own story?

Shapeshifter, swindler and devil’s minion: the red fox is in urgent need of good PR. For thousands of years, the fox has played the villain of folk tales and legends, from Aesop’s fables to Beatrix Potter.

How many animals have had their (alleged) misdeeds immortalised by both a noun (a crafty, cunning person) and a verb (to deceive, mislead and outwit)? “Weasel” and “rat” share this dubious distinction. Informally, the fox has leant its name to an adjective, too – foxy – used to describe an attractive woman, but not necessarily one to be trusted.

The more I saw foxes in the streets where I lived, the more I questioned the popular myths that surrounded them: fox as child-snatcher, cat-muncher, vermin. Fox as scourge of the countryside.

The truth is, we’d got it wrong. Foxes are social animals that pair bond, often for life. Despite a rogues’ gallery of villainous vulpines, they’re usually the victims of a brutal human world. I wanted to give the fox’s side of the story, and that’s what inspired my Foxcraft series.

I first encountered the whiskery ne’er-do-well in the fairytale of the gingerbread man. You know the one – an old woman bakes a gingerbread man who springs to life and escapes her clutches. The little man dodges a succession of farmyard animals until he reaches the stream. Unable to swim, he gladly accepts a ride on a fox’s back. But the fox has tricked his gullible passenger and gobbles him up as they reach the bank.

Another object that springs to life is Pinocchio the puppet. In Carlo Collodi’s cautionary tale, the wooden boy is swindled by a scheming fox and his feline accomplice. If only he’d listened to the Talking Cricket, rather than squashed him with a hammer. What’s that you say? You didn’t realise that Pinocchio killed the cricket? You’re probably thinking of the Disney version.

The illustrated animal stories of Beatrix Potter have been firm favourites with children for a hundred years. In The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck, the foolish Jemima must be rescued from the scheming Mr Tod, a “foxy-whiskered gentleman”.

Mr Tod has echoes of Br’er Fox, Br’er Rabbit’s arch enemy. In perhaps the best-known Uncle Remus story, the fox finally catches the plucky rabbit. He considers the nastiest way to torment his victim. He could roast the rabbit on a spit. He could hang him from a tree. “Anything!” begs Br’er Rabbit, “Just don’t throw me in the briar patch!” A wicked gleam crosses the fox’s eyes as he throws his victim into the briar patch. Br’er Rabbit escapes – “Born and bred in the briar patch!” – but it’s no thanks to the fox.

In the legends of ancient Japan, the fox has supernatural qualities. The Japanese kitsune was able to shapeshift, taking on human form. The kitsune is more attractive than its roguish Western cousin, but both are tricksters – travellers from unknown lands. Each is accomplished in the art of deception. Simply put, the fox is an outsider who cannot be trusted.

In fact, it is the fox who should not trust too easily, particularly an urban cub like Isla, the hunted hero of my series Foxcraft. Isla has to learn mysterious skills meant to help her survive, such as karakking, the ability to mimic the call of other beasts (ever heard a fox cry in the night and thought it was a baby, or a bird?) and slimmering, where a fox becomes invisible for several seconds (don’t foxes spring from nowhere, a flash of red fur beneath street lights, only to dissolve into the dark?). Probably most thrilling is wa’akkir, the shapeshifting foxcraft, inspired by the Japanese kitsune.

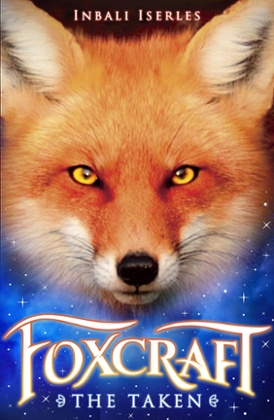

In The Taken, Isla’s den is attacked, her family vanishes, and she’s forced to flee into the night. You’ll have to read it to find out what happens but I hope Foxcraft makes the reader want to run with the fox and hear the fox’s voice. After years of villainous portrayals, of cruelty and smears, I was determined to set the record straight: it’s time for the fox to tell her own story.

Inbali Iserles is an award-winning animal fantasy writer. Her latest book Foxcraft: The Taken, is available at the Guardian Bookshop