Watership Down was the first English book I read of my own accord. I was 16 and had only been learning English “since six years”, as I used to put it in my Germanic way back then. I still used to sit “in the bus”, “do mistakes” and “feel myself sorry” when I made them. Yet Richard Adams’ rabbit odyssey burrowed its way into my heart in the summer of 1997, and I still think of it as essential reading for anyone trying to understand this strange island tribe.

At first I made the mistake of trying to read the novel as another Animal Farm, a political allegory about Europe in the 20th century. It almost works: a group of rabbits flee a collapsing state; they pass through a kind of Weimar Republic warren, blessed with a flowering art scene and a fateful decadence; then an authoritarian warren run by the fascist General Woundwort forces them into a war which they win thanks to the cunning of leader Hazel, the bravery of Biggles-like officer Bigwig, and a resistance-fighter gull with a comical European accent.

I even misremembered the name of one of the does oppressed by Woundwort’s regime, Hyzenthlay, as “Heisenklee” and became convinced that it was a very clever compound of the names of painter Paul Klee and physicist Werner Heisenberg, two great minds discriminated against by the Nazis for their Jewish heritage or pro-Jewish sympathies. In hindsight, I may have had a little bit too much time on my hands that summer.

In fact, Watership Down is much more like A Clockwork Orange: a book so confidently lodged in an alternative universe with its own rules and conventions that it even has its own language. Rabbits here don’t converse in grunts, snorts or howls, they speak Lapine – a distinctly human-sounding language reminiscent of Arabic.

Adams pretends to be our interpreter, painstakingly rendering Lapine concepts into English: the word Hlao, we are told, “means any small concavity in the grass where moisture may collect, eg the dimple formed by a dandelion or thistle-cup”. Tharn is the state of staring, glazed paralysis that comes over terrified rabbits.

The logic of Lapine is not human-down, but rabbit-up. Because a rabbit’s paw has only four claws, for example, they cannot count to five. Any number above four is Hrair, meaning “a lot” or “a thousand”. Concepts of time are defined by the celestial bodies: fu Inlé means “after moonrise”. Any machine, whether car or tractor, is a hrududu.

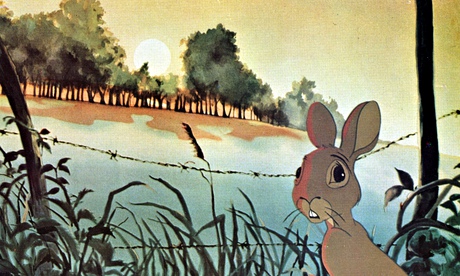

When I mention Watership Down to English friends now, they mostly tell me how intensely they reacted to the 1978 animated film adaptation: how it left them with nightmares of rabbits tearing each others’ throats out, or how much they cried in the scene with the Black Rabbit of Death and that Art Garfunkel song. I got it again when I bought a new copy last week: “Really? It’s such a sad story,” said the woman behind the counter, as if I had just asked her to bludgeon a bunny with her scanner gun.

But I found Watership Down an encouraging book, uplifting even. When I started it, English was another form of Lapine to me: words like “watercress”, “bumblebee” or “culvert” were so alien, they may as well have been rabbit speak. The most cryptic passage in the book was a chunk of human dialogue rendered in Hampshire dialect: “’E won’t be n’ bloomin’ good t’ yer. You put ’im in ’utch ’e’ll only die. You can’t keep woild rabbit.”

But the clever thing about Watership Down is that it it doesn’t just invent its own language, it also teaches the reader how language works. At first Lapine feels awkward. Yet by the end of the book the training wheels have slipped off, and you haven’t even noticed.

During the climax of the siege of Watership Down, Bigwig shouts “Silflay hraka, u embleer rah!” as he launches himself at the enemy. It’s the first time in the book Adams doesn’t provide a footnote, but careful readers can string together a translation: silflay means to feed, hraka are droppings, embleer is to stink like fox, and rah denotes a chieftain or leader. Adams knew what anyone learning a new language eventually realises: once you can instinctively swear in it, you’re cruising.

Migratory lives don’t suit rabbits, the book explains at one point: they are animals built for quick sprints not long marches. Language is like that too, in my experience: you can be fluent in more than one tongue at the same time, yet one of them needs to feel like a home. Watership Down made me believe I could migrate.