Below the line. Three words guaranteed to have struck fear into Guardian writers at some point in their careers. Before the arrival of Comment is Free, writers had a very straightforward – dare I say, satisfactory – relationship with their readers. The writers wrote and the readers read. Occasionally a letter would arrive several days after an article appeared – usually to point out an error, though sometimes to congratulate – but for the most part there was silence. A silence into which anything could be read: a silence that writers for the most part interpreted as a sign that the article they had written was indeed the best thing to have appeared in the newspaper for some months.

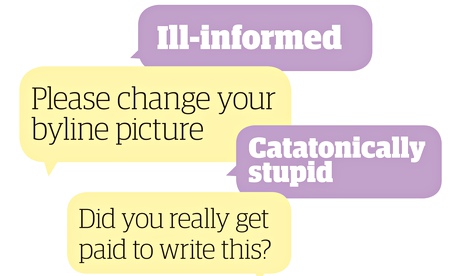

Comment is Free put an end to that particular illusion. It turned out that some readers thought the articles were completely ill-informed and the writers catatonically stupid. “Did xxx really get paid to write this?” is a familiar below the line leitmotif. This is not a line of argument any writers really want drawn to their boss’s attention. Unsurprisingly, it took time for writers to learn how to engage with commenters. Some chose, and still choose, to ignore them and make a point of never responding; others chose to get stuck in.

My own terms of engagement vary. If I am feeling a bit weedy and insecure, I try to stay away from the comments; there are some days when I don’t need my all too obvious defects pointed out. If I am feeling more robust and think I have something to add, then I will join in. It has led to some curious exchanges. Shortly after I was appointed the new parliamentary sketchwriter following the death of Simon Hoggart, it was decided I should have a new byline photo, as the old one was 10 years out of date. Within days of its first appearance, at least a dozen people had commented that the new photo was horrific and frightening. Could I please change it, they asked. I wrote back to say that, regrettably, I couldn’t, as that was what I looked like. The only consolation I could offer was that while they could avert their eyes, I was rather stuck with it.

Some of my below the line interactions have been bruising: online, people are often far more blunt, rude even, than they would dare to be face to face. But far more have turned out to be rewarding. The spikiness of the initial exchanges has turned into something more considered and nuanced; even if neither of us has admitted we were – God forbid – wrong, we have conceded the other may have a point. Several commenters have even become regular email friends. They moan to me about something; I moan back.

Mostly though, I’ve come to realise that below the line is a bit like being trapped in a train carriage full of Guardian readers and drifting in and out of hundreds of conversations. Some are dull and predictable, some are repeats of what was said the previous week and the week before that. But some – most frequently when commenters have long since moved off topic and started their own private/public conversation – are just riveting; as good, if not better, than anything that ever appears above the line. Intelligent, offbeat, deranged and funny. Though sometimes it’s hard to work out just how intentional the humour is.

Marc Burrows has collected the finest and the weirdest below the line contributions and compiled them in I Think I Can See Where You’re Going Wrong. My favourites are: “I know someone who once drank a soy latte and six years later their car got stolen”; “The only thing worse than checking your phone at the dinner table, save for ethnic cleansing and genocide, is pausing live football to have a smoke”; and “Parents should not be allowed to buy books called Baby Names. They forget that they are not naming a cute little baby; they are naming someone who they hope will become a confident, happy 30-year-old. Called Sonny, or Fifi. The books should be called Person-who-will-be-choosing-your-retirement-home Names.”

You will have your own favourites. Every area of Guardian life is here. Seek out and enjoy.

• I Think I Can See Where You’re Going Wrong, edited by Marc Burrows, is published by Guardian Books at £9.99. To order a copy for £6.99 go to bookshop.theguardian.com