Guess what, immigration has been making the headlines again. There has been a dispute about the dirty trade in dodgy statistics which has been going on for years, and controversy over the so-called "racist van" with its blunt "go home" message to illegal immigrants. Once again the complex issue of migration has been reduced to a row about numbers and a war of slogans. We sorely need a more balanced and sensitive conversation about migration, yet political and popular discourses are so poisoned, all attempts at a shift of tone get shouted down.

This is where the arts, and in particular literature, are so important. Throughout history, fiction has been the medium through which we best appreciate that our own experience of the human condition has much in common with the experience of others. For all that we are alone in the world, so is everyone else, and in this way we enjoy (or endure) a shared humanity.

Novels, poetry and plays put us convincingly inside the heads of other people – allowing us to see as they see, think as they think, feel as they feel. These other people may be quite unlike us, they may be people we think that we fear or despise, they may even act in ways that we deplore – but through literature's prism we are able to view their actions from their perspective. The nameless "other" becomes the identifiable "I"; the unimaginably different becomes remarkably familiar.

In the case of a well-written migrant character, we can in some sense experience through them what it is like to leave home and to settle in a foreign country. And, having "lived" through that upheaval vicariously, we are likely to be more sympathetic to those who have actually experienced it. So while reading a good novel about an asylum seeker might not convert us into an advocate of a more humanitarian approach to refugee protection – assuming that this is something to be desired – it will surely give us a greater insight into the human predicaments at the heart of the issue.

It is this more oblique objective that the writer must aim for, even if that writer wishes for a more overt conversion. For the paradox of the political novel is that its contribution to debate comes from eschewing conventional methods. The simple message, the clear line of argument, the obvious dividing line – none of these techniques of communication have any place in a novel. And the author who yields to the temptation to deploy their characters as champions of a cause, however worthy, certainly betrays those characters and their art, but also does little to advance any cause.

It is a pity therefore that even highly accomplished writers – take books by Dave Eggers and Chris Cleave, for example – can be seduced by their own characters into veering down this path. In What is the What and The Other Hand, we are left in no doubt as to where the author intends to shift our sympathies. Yet fiction loses its special power if it seeks to instruct or clarify, rather than losing itself in ambiguity or what the philosopher Richard Rorty called contingency and irony.

It should concern us too that, while the roll call of Granta's best young novelists and the latest Man Booker long list feature so many writers who, in one way or another, are exploring the migrant experience, there is a lack of writing that fearlessly investigates the perspective of the host community, or gives voices to people who feel threatened by immigration.

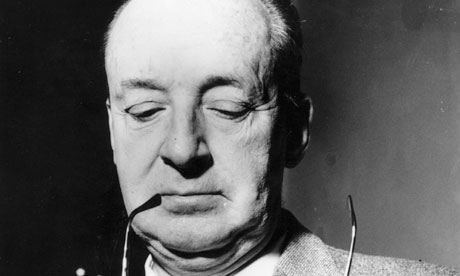

This is not to argue for "the great racist novel", although perhaps the genre needs its own Humbert Humbert. Such a character, both repellent and compelling, would help to illuminate some of the murky corners of this issue, which is one of fiction's great services to us all. Nabokov was famously dismissive of novelistic attempts to write directly about contemporary politics, calling it "topical trash". While the current outpouring of migration fiction surely doesn't merit such scorn, this fiction's best contribution to a debased debate about migration should not be to engage with it, but rather to provide a richer and more humane alternative to it.