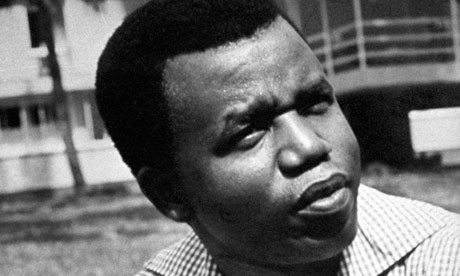

To Nelson Mandela, he was the writer "in whose company the prison walls fell down". To Nadine Gordimer, a fellow Nobel laureate, he was simply "the father of African literature".

The death of Chinua Achebe marks a significant moment in the evolution of literature in the English language, possibly the point at which it has begun to leave behind the bitterness of empire.

Achebe was a great African, but his life and work, from Things Fall Apart (1958) to Anthills of the Savannah (1987), was a long struggle to define himself as an Igbo writer from eastern Nigeria who could somehow find self-expression in the language and culture of a colonial power.

From the seeds of his example hundreds of African literary flowers have bloomed. To a writer such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Achebe's vigorous redefinition of colonialism is less a battle plan than a legacy.

It is perhaps the measure of the change that Achebe helped to bring in his lifetime that much of his career reads like history: born in a British colony; educated as a Christian; recruited by the Nigerian Broadcasting Service; published by William Heinemann; acclaimed by the British literary establishment; caused a storm by denouncing Joseph Conrad for racism in Heart of Darkness. The Nobel prize many expected, and thought his due, did not arrive in time.

Achebe was the leader of a generation, one that includes Wole Soyinka\ and VS Naipaul, that grew up in the dying days of the British Empire. For such writers, the inevitable engagement with the English language was fraught with difficulty.

This CV was acknowledged in the title of Achebe's essays, The Education of a British-Produced Child, but it often got him into trouble with nationalist radicals. Yet, despite his refusal to reject English, Achebe emerged as the essential literary champion of Africa to the wider world.

To millions of readers, he conveyed what colonial oppression meant – in the language of the oppressor. It was a medium that Achebe's unique style, spare, simple and straightforward, made his own.

Through many vicissitudes, including the Biafran civil war of 1967-70, Achebe sustained an enviable artistic serenity. He once said: "I would be quite satisfied if my novels did no more than teach [African] readers that their past was not one long night of savagery from which the first Europeans, acting on God's behalf, delivered them."

Today, with much of Africa, north and south, a dynamic part of global society, that struggle and those ambitions are like something from another age. But Achebe's unique achievement is timeless and inspiring: he found his voice in his own way and used it to bring his world to the attention of the wider world. At the same time, in Nigeria, he gave his people the hope of broader recognition, the special sense peculiar to the written word that they were no longer alone in their predicament.

To many readers, he was a beacon; to writers everywhere a rare example. He once said – in words that should be nailed in letters of fire over the doors of creative writing classes – that "everything is grist to the mill of the artist."

To the end of his life, he was content with his oeuvre: five volumes of fiction, plus essays, poetry and some stories for children. Achebe's wisdom and modesty were a nice antidote to the antics of literary society in some of the richer parts of the English speaking world.