In the late 1990s, easy cash and irresponsibility became an art form. It was the time of the dotcom boom when a small number of clever, usually irreverent and often dysfunctional people invented great things and became billionaires overnight. Some became mainstream corporate bosses; others would disappear off the map. One of those who made silly amounts of money and then blew it all was Josh Harris.

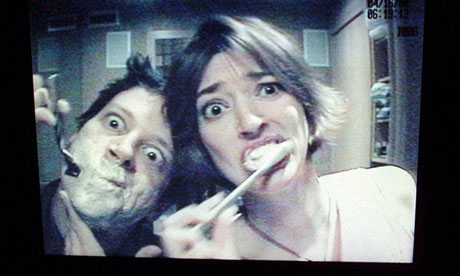

Harris was one of the early pioneers (bathos intended) of Big Brother-style reality television. His career culminated and collapsed in 2000 with the filming of his life, and that of his girlfriend, in a real-life internet show called We Live in Public. Everything they did, from sex to cooking dinner, was filmed and made available for anyone to see. He wanted to conceive a child online. "Think about it, wouldn't you enjoy sex more if you knew you were being televised?" Eventually his girlfriend, Tanya Corrin, became fed up with him, walked out and tried to get the rights to the hours of digital "performance art". This was the merging of counterculture and cyber-culture. This was New York's Silicon Alley at its peak of bling and hedonism.

Harris's parties were chronicled in magazines around the world. An earlier project involved inviting around 100 people to his warehouse apartment, so big you could line up several double decker buses in it, for a collective social experiment in wired living. It was busted on millennium night by anti-terrorist cops fearing it might be a suicide cult.

You might wonder why Harris's life story requires a book. But when I finished reading Totally Wired, I understood why the cultural journalist Andrew Smith had written it. This was a slice of life never to be repeated. Smith followed Harris for years, eventually catching up with him in Awasa, an Ethiopian town where he had gone to hide from the cacophony he had engendered in New York. "The thing about life in deep Africa is that every day is a life-and-death experience and your senses get sharp," Harris tells Smith. "New Yorkers think the world's ending if they can't get dinner reservations at the right restaurant."

Smith traces the start of the internet generation, providing fascinating passages about some of the forgotten individuals (such as the 1960s military programmer JCR Licklider – "Lick to his friends"), and the startups that quickly went flat. "The first people to recognise the social power of the online idyll were the former flower children," he writes. The book is peppered with enjoyable anecdotes. "The first online business transaction," he notes, "is said to have involved a quantity of dope shipped between students at MIT and Stanford circa 1971."

By the mid-1990s, irrational exuberance had taken over, from the party-goer, to the nerd, to the investor, to bankers such as Alan Greenspan. The first initial public offering of shares was Netscape. And it went completely wild. From that point there was no going back. In 1997 Wired, the bible of the emerging online community, declared: "We're facing 25 years of prosperity, freedom and a better environment for the whole world." Nasdaq, the US technology stock index known affectionally as "Nazz", couldn't stop rising. Some firms were valued in multiples far greater than their worth. As they partied and saw their fortunes soar, one chief executive warned his colleagues: "This won't last for ever, enjoy it and remember it!"

Then came 2000 and the dotcom crash. Some retrenched, survived and went on to thrive. Others, like Harris, did not. He insisted his corporation, pseudo.com, was actually fake. He could not, would not, allow his mind to enter the "grown-up" business world. He preferred to host endless parties, interviewing characters about foot fetishism for his online show, and persuading the French champagne industry to sponsor a happening entitled "The End Is Near".

Smith describes him as a modern-day Gatsby. Harris likens himself to a Warhol of the web. His friend and fellow indulger, Jason Calacanis, said of him: "He's one of the 10 most important people in the history of the internet and nobody knows who he is." Unlike Mark Zuckerberg and his ilk, with the world at his feet, Harris threw it all away, and seemed happy to.

I wasn't sure in the end if I admired him for his refusal to be boring or if I scoffed at his self-indulgence. I suppose the answer is a bit of both. This was an age of excess and innocence unleashed by the breaking of financial and communications barriers. Even the Clinton administration, which bought into the optimism of the moment, was worried by the loss of state control. It was the first government to try to establish surveillance over all electronic traffic, via a so-called "clipper chip", which was seen off technically by the cyber geeks.

Now, more than a decade on, the authoritarians are far more successful in watching, listening and following us online. The internet is much more sober now.

John Kampfner is author of Blair's Wars and Freedom For Sale