TonConoboy: Is your application of myth essentially positive about humanity, or do you ascribe to the notion that myths reveal a darkness in the soul of man?

Alan Garner: Yes, to both.

GalleyBeggars: I read once that you don't like to reread your own books. First, is that right? And if so, why? Following on from that, did you have to reread The Weirdstone of Brisingamen to write Boneland? I ask particularly because I know you once said you didn't think it was a particularly good book and I'm wondering if you've changed your mind …

AG: I don't reread, unless I have to (eg for adapting The Owl Service and Red Shift for television). Once my duty to the text is finished and it's published, I've no interest in looking at those words for the nth time. The book must find its own way. I have to move on.

BryanFerry: British oral traditions are clearly important to you. You seem to have become our most prominent curator and champion of folk tales with your editorship of anthologies, and written contributions to the field (I loved Yallery Brown). And of course your novels, both children and adult, that draw on this mythology. My question: why do you think such a big chunk of British cultural heritage has come to be so overlooked and neglected?

AG: Hard to answer in brief. Some of the reasons are the breaking up of rural communities and the diaspora into cities as a result of the industrial revolution; the watering down of traditional tales for use, and control, in the nursery; the appropriation by scholars, resulting in arid prose not intended for an audience. There's much more at work. Yet hope lies in the modern movement of oral professional storytelling. There's sap in't yet.

FatherHackett: The Trickster figure is important in your work (not just explicitly in the Guizer but implicitly in characters such as Tom in Red Shift and in many of your shorter works). How much of a Trickster is the Author? Where does the play of meaning and appearance end, or is it all seamless?

AG: The Author IS Trickster. The play of meaning and appearance should be seamless. I unwittingly spend a lot of time and energy on this.

Galabackhome: The stories are strongly rooted in the places they are set. Are these places that have special personal meaning to you prior to the story; or is it the myth associated with the place that breeds the story?

AG: Place comes first, and the rest is exposed, as if in an archaeological dig.

Jericho999: What do you think about Alderley Edge nowadays? Does its reputation as a Wag paradise change your feeling about the place?

AG: Alderley Edge has always been a fake. Its real name is Chorley, which didn't suit the textile barons of Manchester (Lord Stanley called them "the Cottontots"), who came with the advent of the railway in 1841. It's a place that has always attracted new money. The difference in the 19th century was that some of the commercial families were philanthropic and cultured. That doesn't apply now. The old, working and craft families, from whom I come, occupy the same geographical co-ordinates but not the same world. "We" let "Them" get on with being transient. Welsh has a definition of the kind of people to whom I belong, which translates as "a man of his square mile". We know our place.

Monkeynotdonkey: One of the things that really fascinated me and also slightly disturbed me when I read Elidor as a boy was the sense that the entire mythology appeared to have sprung complete and fully formed from nowhere. It didn't fit with my then quite limited knowledge of myths and legends. As I've grown up I've recognised elements of the tale in existing folklore. How important was it to create an independent mythology for Elidor, and how much of it was drawn from other sources?

AG: The background to Elidor is an amalgam of linked pre-existing mythological themes (all myth pre-exists), which I wove into a tapestry of story.

Imogen Russell Wiliams: I was amazed and heartened, as a great fan and fellow sufferer, to discover you had been diagnosed with manic depression during your career. How much has bipolar disorder hindered you in your work, and has it helped you at all?

AG: I am not qualified to comment, and it would be irresponsible of me to try.

SimonNorrton: Growing up in Cheshire, the Edge, its legend and your stories were a hugely influential part of my childhood and teenage years – as they have been for so many others – and coming back to the stories once again in anticipation of Boneland has revealed new layers of meaning for me, particularly through your By Seven Firs and Goldenstone paper. May I take this opportunity too, to express my appreciation of your work. I've recently completed a masters degree and focused in part on fairytale and storytelling and your work has brought "my/our" local story that much closer to my heart. Thank you.

I wondered how recent archaeological work at the Edge had added to your understanding of the area. I wonder if there might be a relationship between the Sleepers and the Barrows.

AG: Thank you. The By Seven Firs and Goldenstone paper is the only truly original work I've done, and even there I missed an important trick, which I've now incorporated in the revised, but not yet republished, monograph.

You've got it back to front. It was my understanding of the Edge that led, after 40 years of badgering the academics, to the proof of the archaeology.

DebbiUK: I've always wondered if Findhorn had to die because Helen broke the jug.

AG: Traditionally, the unicorn can be caught only when it lays its head in the lap of a virgin. The jug is up to the reader to interpret.

AllanFrewinJones: I've been a reader of your work since I was awarded Weirdstone for good attendance at Sunday school when I was 10. I was inspired to become a writer by reading your books and I now have them on audio CD as well as in hardback. As a children's writer, I go to schools from time to time, and I always tell children to seek out your books. A friend texted me last week, asking which of your books I would recommend to a 12-year-old boy. I said, if he's interested in girls, give him The Owl Service, if not, Weirdstone. Here's my question: do you write with a specific external audience in mind, or you you write primarily to produce work that (temporarily at least) pleases and fulfills your own muse/intent? Or, to put it another way: is an external audience integral to your work?

AG: At the time of the writing, the external audience is unknowable and has no influence on me or the work.

Alberich: Alan, was there any specific inspiration for the Mara in The Weirdstone of Brisingamen? I've always found their first brief appearance one of the most haunting and terrifying passages in literature. And do they reappear in the third book?

AG: Henry Moore's sculptures of reclining women scared, and still scare, me.

Palparadise: I was wondering if there are – other than Alderley Edge – subjects, areas of interest, both physical and psychological (in its loosest sense) that are important to you, particularly in regards to your writing of fiction?

On reflection this sounds like such a horribly narrow-minded question, considering the themes and subject matter you involve your readers in. Sorry about that. What I mean to ask is whether you have any interest in taking your characters to other places, beyond folklore, beyond myth, legend … Is there a beyond? I'm not sure. Crikey, I've not made myself clear at all but I can't seem to delete my original question.

I love your fiction; it's been/is very important to me. Thank you.

AG: I find your question hard to understand. But there is no beyond.

Lord Snooty 12: I apologise for asking three questions, but you don't have to answer all of them.

What do you think you would have done with your life if the WOB had stayed in the slush pile?

I find it interesting that The Owl Service was published in the UK in the same month that Sergeant Pepper was released. There was clearly an enormous surge of creativity at the time. What's your verdict on the 60s?

How many plates with The Owl Service design have you come across over the years?

Thank you.

AG: I'd have carried on writing. There is no option. It's not a job but a condition.

I was too busy to notice the 60s, or any other decade. The genesis of an undoubted release of creativity into all areas of society was the 1944 Education Act; which enabled me to have a free education at a fine grammar school, and a free education at one of Oxford's best colleges.

Five. The designer was recently identified as Christopher Dresser.

Cazzaminx: Boneland – why now? Simple question, but I've been imagining all manner of possibilities. Can't wait.

AG: Because that's how long it took. The other books had to be written first. Essentially, the nine novels are all one work.

Redridinghood19: My question is about the act of writing, creating a story in your mind. Do you find that stories – the best stories – simply spring up in front of you, almost fully formed?

AG: Every writer has to discover their own way to write. In my case the sensation is that the stories find me. If I were to go looking (which I don't) they'd not be there. Experience has convinced me that the conscious mind is a fine editor and critic, but is entirely unoriginal. Creativity is the product of the unconscious. I "see", "watch", "listen", and write it down, with no intellectual planning. What happens is as new to me as it is to the reader. It's also essential, for me, to read the text aloud. If it jars the ear it will jar the mind.

Thackur: Your writing style is famously economical with words and carefully crafted. Indeed the theme of craftsmanship is crucial in works such as the Stone Book Quartet. So is a lot of your time spent revising and honing individual sentences – do you write "like Alan Garner" quite naturally or is it a matter of a lot of hard graft in the workshop, chiselling away at the sentences, with a lot of words ending up on the cutting-room floor (to mix my metaphors in a very un-Garner-like way)?

In similar vein, is a lot of the writer's art knowing what to leave out, so drawing in the reader's own imagination to fill the gaps? There's something wonderfully sinister about the unseen mother character in The Owl Service.

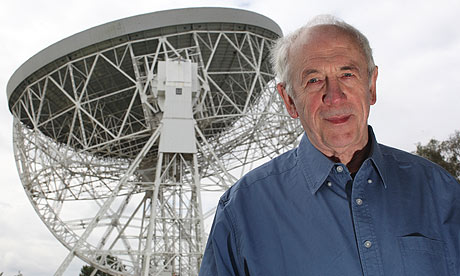

I'm interested to see Jodrell Bank taking a central role in the new book. I've always thought of it as an unmentioned presence in Red Shift, which seems to me like a series of distorted transmissions from across great distances of time and space, picked up in (or originating from) modern day Cheshire. Has it always been as much part of your imaginative landscape as the ancient folklore, having this great device for listening to the universe sitting on your doorstep?

Very excited about the new book … Thanks.

AG: Every word has to beg for its life. Adverbs and adjectives are born guilty until proved innocent. When something is "finished", I cut it back, and continue until what is said can be said in no fewer words. This leads to clarity and impact, and also to an extra dramatic effect when the rule is broken and the words appear to run riot. They don't. They're on a strong leash. (There are examples of this in Boneland.)

The reader will benefit from having to engage actively, too. If I've got it anywhere near right, each encounter with the text will provoke a creative response and interpretation in the reader that may not be there for me because I've not had that reader's experiences.

I've lived less than a mile from Jodrell Bank for 55 years. I'd have to be made of granite for that not to have had an effect. The Lovell telescope is one of the world's great works of art. And totally functional.

Sam: I've been reading Boneland and have found it a very hard read – in the best sense of that term. It's raw, vivid and hits you right in the gut, on an emotional level. I'm wondering if it was also especially difficult to write. I know writing never comes easily – but did this one hurt more than others?

AG: Thanks for the compliment that counts. Every book's the hardest yet, but this one IS the hardest.