A long long time ago, back in the early 1990s, there were only three novels about Edinburgh. There was Robert Louis Stevenson's The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll & Mr Hyde (which wasn't actually set in Edinburgh at all), there was James Hogg's Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner and more recently Muriel Spark's The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. The Scottish capital had plenty of other books to its name but those were the only three that mattered, the ones that knocked through all of Edinburgh's lovely false fronts to the far more interesting things behind.

Forty miles away, there were writers falling over themselves to talk about Glasgow: James Kelman, Alasdair Gray, Jeff Torrington, AL Kennedy, Janice Galloway. Somehow, Edinburgh's great rival just offered more to describe – more people, more history, fewer layers to scrape off between appearance and truth. Glasgow was cool, and whatever Edinburgh was – beautiful, vertiginous, cold – it had never in its whole life been cool.

And then in 1993, a book called Trainspotting was published by an unknown council worker called Irvine Welsh. Trainspotting told the story of another Edinburgh entirely; not the pretty neoclassical bit in the middle, but the schemes and estates beyond the invisible Pale – places like Saughton and Niddrie and Sighthill which had been used by the Tories to test out contentious new ideas: closing the car plants, bringing in the poll tax, flooding the neighbourhoods with cheap high-grade heroin… By the time Trainspotting came out, Edinburgh had stopped being the Athens of the North and become instead the Aids capital of Europe.

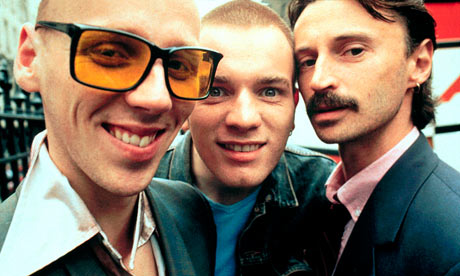

If Welsh had set his novel in Glasgow, there would have been a brief fight about swearwords and then silence. Because he set it in Edinburgh, Trainspotting went off like a detonation. It was written in a thick Leith accent and it told the stories of a bunch of neds and schemies on the hunt for dole, sex and junk. But Trainspotting's real brilliance was the zest and joy and sheer black-hearted energy of its writing. Now, nearly 20 years later, it's difficult to imagine Scotland without the psychopathic Begbie or Bond-obsessed Sick Boy, or Renton's echoing lament: "Some hate the English. I don't. They're just wankers. We, on the other hand, are colonised by wankers…"

Britain loved Trainspotting, Scotland loved the spectacle of Edinburgh with its knickers off, and the city itself remained ambivalent. On the one hand, the revelation that it had as many issues with sectarianism and STDs as the wild wet west irritated the New Town enormously; even now, the official Edinburgh Unesco City of Literature website pays Trainspotting the great compliment of completely ignoring it. On the other, most people soon realised that Welsh had somehow pulled off the trick of conveying a pungent anti-drugs message while simultaneously making Edinburgh look interesting. Suddenly the place was full of Fettes boys hanging out at the Foot of the Walk and talking radge with their swedgin and barry.

Anyway. All that said, what exactly is the point of Skagboys? Welsh can never be unknown again. His writing can never shock like it once did. No prequel or sequel can have the impact of Trainspotting. Ecstasy – his 1996 follow-up – didn't exactly tank, but nor did it reach anywhere near Trainspotting's giddy heights.

And first impressions aren't great. Skagboys is long: 548 pages in hardback. There are a lot of characters and too many voices. Sometimes, when Welsh slips back from Edinburgh to English – as he does with Renton's parents – the deficiencies in his fiction become obvious. Worst of all, there are signs that he's using Skagboys as a teaching aid. Brief socio-historical pass notes are included every couple of chapters for the benefit of anyone too young, too posh or too English to have noticed what was happening to Scotland during the 1980s. Optimum laboratory conditions, in other words, for a disastrous read.

Except that Skagboys isn't. We start out back in the days when Mark Renton is clean and reading for joint honours at Aberdeen Uni. He and Sick Boy take their first fix. Renton's brother Wee Davie dies. The heroin begins to take hold. His family begin to disintegrate and the good girls fall away. He drops out of university and goes to work on the boats. "Schopenhauer was right," Renton thinks: "life has tae be aboot disillusionment; stumbling inexorably towards the totally fucked."

For anyone who loved Trainspotting first time around there's something deeply cheering about returning to Welsh's world. "Are you sexually active?'' asks the woman at the Aids clinic. "Usually, aye, Keezbo goes, no gittin her at aw – but sometimes ah jist like tae lie back wi a bird oan top…"

For those who want to be shocked, there's plenty of provocation – Renton tossing off his "spasticated" brother, puppies down rubbish chutes munching on aborted foetuses, a memorable incident involving budgies and a mastectomy – and plenty of perfect moments: Renton torn by "resentment and tenderness" beside his grieving parents, Begbie raging at others for admiring his singing voice, Renton and Sick Boy wound round each other like bindweed.

And many of Welsh's wider points are well made. His "Notes on an Epidemic" include a couple of monthly lists of reported HIV-positive cases: 39 names, each with their terrible case histories summed up in a sentence. "If being Scottish is about one thing, it's aboot gittin fucked up," Renton explains. "Tae us intoxication isnae just a huge laugh or even a basic human right. It's a way ay life, a political philosophy."

And then things go slack and you can sense Welsh's concentration wandering. Twenty years later, he's too far from a world he was already distanced from when Trainspotting came out. Besides, part of the problem of writing about drugs is that almost by definition, every fix gets a little less interesting: heroin, like happiness, starts to write white. For hardcore enthusiasts, Skagboys' more measured pace and broad overview is a treat. For everyone else Trainspotting said it all, and said it better.