"Coming up with a name was far more difficult than we expected," says co-founder Rosalind Porter of the birth-pangs of new publishing venture Union Books, also headed by Alex Clark and David Graham and due to be launched next week. "The three of us went round in circles for months pushing our favourites.Alex's Bloomsbury sensibility informed all her suggestions; David's love of dogs was never far from his; I kept returning to the binomials of poisonous plants, which were by far the least popular."

Eventually, though, the trio settled for the recently popular option of borrowing the name from a place: "We'd often meet at the Union club [in London's Soho] to discuss the imprint, and one day Union simply became the strongest contender."

Naming the imprint after themselves was clearly unthinkable, as it was for those behind two more start-ups launching this spring, the relatively conventionally named Bloomsbury Circus and the eyebrow-raisingly adventurous Head of Zeus. Yet that was the norm from John Murray in the 18th century to Faber & Faber at its birth in 1929, conveying the assurance that (as with Mr Kipling's cakes) the books had been personally selected and vetted by the owner; or more often owners, as two names were so preferable that Geoffrey Faber added a non-existent relative to his firm's monicker and the obscure poet WE Windus, though merely Andrew Chatto's sleeping partner, gained a kind of immortality.

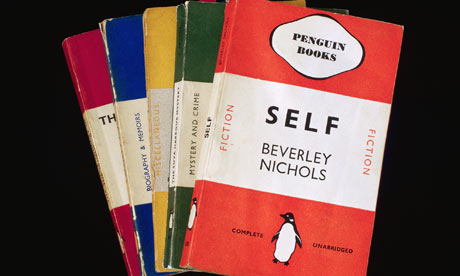

This convention, mocked in Private Eye's Snipcock & Tweed cartoons, left a legacy of lists still around today, from Jonathan Cape to Weidenfeld & Nicolson, Hamish Hamilton to Harvill Secker. But soon after Faber's launch came the arrival in 1935 of Allen Lane's Penguins, which not only introduced paperbacks but altered how publishers presented themselves – not a couple of literary chaps sending out dusty tomes, but a bird Lane chose as a "dignified but flippant" symbol of paperbacks' difference from heavy, less portable hardbacks, and which was lent a sense of being at ease with modernity by the previous year's opening of Lubetkin's Penguin Pool at London Zoo.

Penguin-mimicking single-word symbols soon became the norm, whether other animals (Bantam, Corgi), derived from myth (Pan, Orion), or figures (Picador, Viking) or objects (Sceptre, Arrow, Carcanet) embodying hoped-for values. With the 70s and 80s came the imprint name as statement of intent – Virago, Bloodaxe, Serpent's Tail – and counter-culture affiliation; with 90s property-fixation came the soberer fashion for places, as with Bloomsbury and the revitalised Canongate (after a district in Edinburgh, where the company is based). Weidenfeld apart, John Blake's ultra-populist list (Katie Price and royal biographies) and (Christopher) MacLehose Press's ultra-literary one (which has made a fortune for Quercus, of which it is part, by publishing Stieg Larsson in English) are the most prominent of the few remaining examples of publishers named after living bosses.

Names are rarely changed, with the result that the UK's three leading conglomerates have labels that today look ill-advised. Hachette unpromisingly means "hatchet"; Random House was so-called because its originators designed it "to publish a few books on the side at random" alongside their main imprint, but has become the world's biggest trade publisher; we now think of penguins affectionately but as comical and flightless – clumsily ill-adapted, not slick and up-to-date.