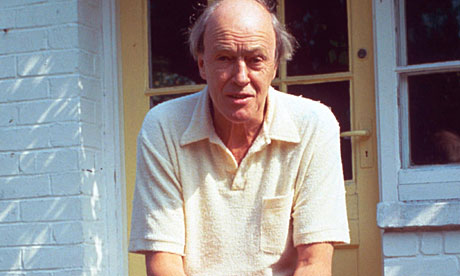

With Roald Dahl again in the news after his family launched an appeal to save his famous writing shed, a good time to reassess his life and career with the paperback publication of Donald Sturrock's Samuel Johnson prize-shortlisted biography, Storyteller: The Life of Roald Dahl (Harper Press). "No matter how you spin it – and at times Donald Sturrock spins quite hard", wrote Kathryn Hughes in her Guardian review, Roald Dahl was an absolute sod." Sturrock is the official biographer, authorised by the Dahl estate, but the "result is by no means a whitewash" explained Hughes, more "an attempt to nudge the picture in favour of a man who, despite so many reasons to dislike him, remains one of the greatest forces for good in children's literature of the past 50 years."

Another prolific writer, and difficult man, in Phil Baker's The Devil is a Gentleman (Dedalus), his biography of Dennis Wheatley who might be almost unread now, as Chris Petit pointed out, "yet for 40 years he was as famous and popular as anyone, with 20m sales, standing in today's terms between Jeffrey Archer, another self-made author who wrote his way out of financial trouble, and Dan Brown, whose cod esotericism is close to a steal." Wheatley's thrillers and occult stories were written for "material success and to ingratiate himself with those he perceived to be his social betters," said Petit. "There was also an unlikely friendship with Anthony Powell, who had him down (not unkindly, given how he rated other writers) in the category of 'relatively intelligent men who write more or less conscious drivel', but considered him sufficiently skilled to seek plotting advice from."

Wheatley's occult bunkum once passed itself off as a representation of evil. The real thing is the subject of Bloodlands (Vintage), Timothy Snyder's forensic study of the deliberate mass murder of civilians in the killing fields of central Europe from the start of the second Ukraine famine in 1930 to the end of the second world war in 1945. "14 million innocent human beings, most of them women and children, were shot, gassed or intentionally starved to death", said Neal Ascherson in his review.

Out of the unimaginably colossal scale of the atrocities Snyder deftly plucks out individual stories. "The Nazi and Soviet regimes turned people into numbers," he says. "It is for us as humanists to turn the numbers back into people."

Two fascinatingly detailed music books also emerge this month. John Szwed's The Man Who Recorded the World (Arrow) tells the story of Alan Lomax, the pioneering American musicologist whose field recordings of American folk music saw him play a pivotal role in the careers of Lead Belly, Muddy Waters, Woody Guthrie, Burl Ives and many others. "Disorganised in his private life, Lomax was the most meticulous of researchers into folk culture," wrote Richard Williams in his review. "The result is an extensive portrait of a brilliant and difficult man who, astonishing as it may now seem, spent most of his career battling the indifference of those in a position to help him preserve the irreplaceable."

Music writer Norman Lebrecht exhibited similar intensity of purpose in his Why Mahler (Faber). "A most peculiar enterprise," said reviewer Stephen Moss, "which mixes biography, travelogue, CD guide and rather too much autobiography … yet the sheer exuberance of the writing makes you forgive the lack of organisation and the decision to write the book in the present tense, which Lebrecht justifies on the grounds that Mahler is 'a man of my own time'."

Other books just out in paperback this month include Doris Langley Moore's account of Byron's posthumous reputation, The Late Lord Byron, Thaddeus Russell's A Renegade History of the United States, which highlights how drunkards, prostitutes, criminals and other outsiders shaped American society, and Ancient Worlds, in which Richard Miles traces the evolution of civilisation in the Mediterranean region.

Finally Just My Type by Simon Garfield (Faber) which Jonathan Glancey described as "an engaging book setting any number of stories – those of John Bull printing outfits, Nazi German lettering, Letraset, punk typography and the wretched London 2012 Olympics font ("the sort of lettering you will find at London kebab shops and restaurants called Dionysius") – in highly legible, and very readable, Sabon MT 11/15pt, designed in Leipzig in the 1960s by Jan Tschichold."

Just for your info, the font you are reading now will depend on whether you are on the web, or a Kindle or an Android phone or an iPad, etc etc etc ... But whatever the font, do let us know what you think of the books above, or any other paperbacks you're looking forward to reading this month.