As a child, Tobias Wolff rode shotgun across 1950s America with his single mum at the wheel. They were in search of adventure, on a mission to prospect for uranium and make themselves rich. Instead, Wolff found himself marooned in small-town Concrete and oppressed by a brutish stepfather, until he finally sat down to concoct the letters of recommendation that won him a place at an exclusive East Coast school. Those letters, in hindsight, can be filed as his first great work of fiction.

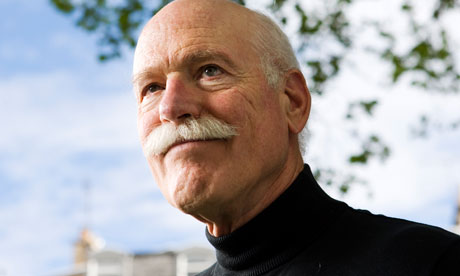

Wolff is the writer who wrote himself into being, and who did it so well that the trick became the truth. These days, with his burnished bald pate and frosted sagebrush moustache, his seat at Stanford and his headline status at the Edinburgh book festival, he looks every inch the literary heavyweight. For all that, he still struggles to shake the fear that he will one day be rumbled, found out, exposed as the hubristic kid who told tall tales. "I still feel as though I'm faking it, but maybe that never goes away," he admits, sitting outside in inclement weather by the authors' tent. "I'm sure I disappoint my students on a daily basis. They expect me to talk about great books and big ideas, whereas a lot of the time I want to talk about baseball. My banalities are always alarmingly exposed."

Fortunately Wolff has been adept at managing the exposure, in framing it as drama. He documented his troubled, itinerant childhood in his breakthrough memoir, This Boy's Life, spun his student years into fiction in his deft 2004 novel Old School and revisited a subsequent tour of duty in Vietnam with In Pharaoh's Army. Along the way he has become aware of the pitfalls; alive to the dangers of putting your life on the page. "There's a great article by William Gass entitled The Art of Self: Autobiography in an Age of Narcissism, in which he says something along the lines of 'he who writes an autobiography has already made themselves a monster'," Wolff says. "And of course, it involves a certain ruthlessness, a certain structuring of the material in the service of the story. In the case of This Boy's Life, I probably overcompensated with regards my boyhood self. I so didn't want to paint myself as some little orphan Annie, this sensitive bookish type, that I possibly made myself more troubled and unruly than I was." He grins. "Whereas, in actual fact, I probably was a sensitive, bookish type."

What did his mother – the memoir's other central figure – make of his account? "I remember she gave an interview in which she said that it was 85% accurate," he says. "I figured that was a pretty good result. The objections she had were more questions of detail than of judgment. She'd say: 'Now you wrote that the dog was ugly. But that dog was beautiful.' But she was fine with the way in which she was portrayed. She told me that she was glad I hadn't glossed her, cleaned her up, made her better than she was for public consumption, because that would have meant I didn't accept her as she was. I found that touching."

The teenage Wolff briefly adopted the name of Jack in honour of Jack London, and freely admits that he honed his craft by aping other writers. "Well, imitation is always the first step to achievement," he shrugs. "You learn to walk by watching people walking. I have a son who plays tenor sax. He started out copying, you know, Dexter Gordon or Coleman Hawkins. After a bit of that you hopefully begin to find your own voice."

In Old School, Wolff even went so far as to ventriloquise his idols. The book arranges entertaining cameos for the likes of Robert Frost and Ayn Rand, while Ernest Hemingway, half-cut, railing and pointed towards death, promises to visit the school only to bail out at the last moment. Hemingway, he says, remains the great perennial. "He's such a dominant figure in American literature; you can't ignore him. He's papa, the great father, and you find that you either have to revere him or kill him. But the work is what counts and the work endures. The short stories, in particular, I still find astonishing."

Wolff has likewise been lauded for his short fiction. I particularly love In the Garden of the North American Martyrs (in which a sacrificial job applicant turns the tables on her tormentors) and Hunters in the Snow (in which a shooting trip pitches, by degrees, towards acid-black comedy). I've read that he once said the short story was the perfect vehicle for American fiction. "Did I?" he frowns. "Well, maybe there's some truth in that. Apparently 80% of Americans move home at least once every five years. It's a transient culture, so maybe the form is peculiarly suited to catch the experience. But obviously there are great American novels too. Gatsby, to name but one."

The writer is now 66, five years older than Hemingway when he died. He laments that he has been nothing like so prolific. "I'm too fussy, it's true," he says. "Though one should always resist comparing yourself to other writers. You go crazy that way."

At some point, he says, he would like to tackle another memoir. He recently read a book about literary life in 1940s Dublin and fancies writing something in a similar vein, about the writer's place in 21st-century America. Are there any obvious comparisons? Wolff laughs. "Well, there's less alcohol than there was in Dublin, that's for sure. In fact, that's been one of the big changes during my time as a writer. We all grew up inspired by men like Hemingway, Faulkner, Fitzgerald and Robert Lowell – all of these great authors who drank too much and led these troubled lives. But then, over a period of about four or five years, the whole culture shifted and the drinking just stopped. So writers in America today are very different. They live on the campus, they're supported by the universities. It's all extreme health with them. It's about energy drinks and running programmes."

On the face of it, this doesn't sound the most inherently dramatic world to write about. "Yeah well, that's the issue," he says, basking in a rare burst of Edinburgh sunshine. "Things going wrong: that's usually good material to work with. When things go right, when life is good, it's rather less exciting." And this, perhaps, is the logical end of Wolff's Horatio Alger-style rise through American letters. He may now have reached the point where he has written himself clean out of the memoir game.