I have been reading Every Printed Page Is a Swinging Door, a privately printed catalogue of the experimental poet David Gascoyne's library, compiled by the eminent bibliophile and rare-book dealer James Fergusson. Such catalogues combine many secret pleasures: the fascination of old texts, arcane references and rambling footnotes. As well as the literary scholarship crammed into its 200 pages, this £10 paperback reads like an elegy to a lost world, an extraordinary chapter of 20th-century literary history now in the antechamber to oblivion.

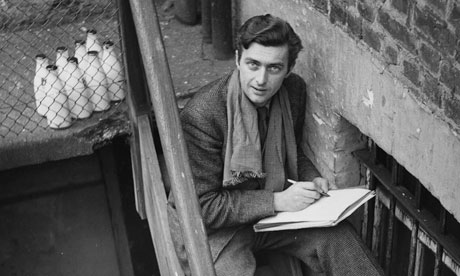

David Gascoyne was born in 1916, the son of a bank clerk, but with some artistic antecedents. His mother, Winifred, was one of two young women who witnessed the death by drowning of the dramatist WS Gilbert in 1911. His first book, Roman Balcony and Other Poems, appeared in 1932, when he was just 16. A novel, Opening Day, was published the following year. Both signalled remarkable precocity.

But it was Gascoyne's work as a surrealist that consolidated his reputation, especially Man's Life Is This Meat and his work on the International Surrealist Exhibition in London in 1936. This included an event where he had to rescue Salvador Dalí from suffocation in the deep-sea diving suit in which Dalí was attempting to lecture (don't ask).

Self-taught, restlessly original and extravagantly gifted, Gascoyne was a member of a scattered community that included Charles Madge of Mass Observation, several British communists and AR Orage, the editor of New English Weekly. Gascoyne was an omnivorous bibliophile, as this catalogue illustrates, flitting between the reading room of the British Museum and the now vanished bookshops of the Charing Cross Road. If there was a British avant garde in the 30s and 40s, Gascoyne and his publisher, Tambimuttu, were among its leaders. Gascoyne's milestone collection, Poems 1937-42, established him for some readers as the poet of the age.

However, in the lottery of a poet's career, Gascoyne drew the short straw. He had the misfortune to be publishing during the boom years of Auden, Spender, MacNeice and Day Lewis. The surrealists became marginalised by the public and lampooned by the up-and-coming generation led by Dylan Thomas. "I am a poet who wrote himself out when young and then went mad," Gascoyne said in later life. But he never lost his appetite for squibs and pamphlets. His library illustrates a life devoted to offbeat publications and unlikely enthusiasms.

There are names here that were once braided into contemporary literary consciousness, but now fallen into neglect: Kathleen Raine, Jeremy Reed and Pierre Jean Jouve. Every Printed Page is a snapshot of a lost world: numerous volumes of Penguin Poets, editions of now-forgotten little magazines. In the age of the app and the ebook, it's hard to imagine such a world of print surviving another century.

This catalogue is also the record of a love story. By the 1970s, as Fergusson describes, this mendicant, artistic introvert whose future was behind him collapsed from a combination of amphetamine addiction and depression. Eventually, he was hospitalised in a converted asylum in Newport on the Isle of Wight.

Judy Lewis, an energetic housewife of fiftysomething with four children, used to read to the hospital patients. On one occasion, she told her class that "we're going to read a poem [from The Oxford Book of English Verse] by David Gascoyne". The tall, sad-looking man who sat next to her touched her on the arm and said: "I wrote that poem. I'm David Gascoyne." Judy replied: "I'm sure you are, dear." Two years later, they were married.

Their mutual inscriptions to each other on the fly leaves of the books in this library are immensely touching, a proof that late-flowering love can be just as romantic as youthful passion. Married to Judy, Gascoyne recovered some of his mojo. It's a nice irony that the poet who burst on to the scene in his teens should find fulfilment in his autumn years.

David Gascoyne was, as Craig Raine put it, a "vieux jongleur and history man". He died in 2001. This little book might mark the beginning of a belated posthumous rehabilitation.

Every Printed Page Is a Swinging Door, £10, jamesfergusson@btinternet.com

What – a literary prize without controversy?

When the Irish publisher Desmond Elliott was fired 10 days before his 30th birthday, it looked like the end of a promising career. In fact, it was the making of him. When he died in 2003, he had become one of the most colourful and successful figures on the London literary scene. Happily, his spirit lives on in the fiction prize that bears his name. Last week, in the improbable setting of Fortnum & Mason, London, Edward Stourton and a distinguished jury awarded the fourth Desmond Elliott prize to Anjali Joseph for her novel, Saraswati Park (Fourth Estate). Stourton apologised for failing to generate any controversy in the judging process. It was, he said, a unanimous decision.

So Kate Middleton's a real Austen heroine

It did not take long for the genealogy buffs to prove that Prince William's wife, Kate, is a distant relation of Jane Austen. Apparently, the new Duchess of Cambridge and the author of Pride and Prejudice are 11th cousins, six times removed through their 15th-century common ancestor, Henry Percy, who was the 2nd Earl of Northumberland. This connection is fitting. Austen's female characters are always falling in love with, or aspire to marry, men of higher rank. That's the best-case scenario available. Unlike George IV (a great Austen fan), there's no evidence that the current royal family have any interest in English literature. Now that we know Kate's connections, perhaps Flying Officer Wales will swap his helicopter manual for copies of Sense and Sensibility or Persuasion and even make the pilgrimage to Chawton House.