Alice Prin was the model known as Kiki, immortalised by myriad artists including Fernand Léger, Jean Cocteau, and her lover, Man Ray. It seems fitting that her latest biography should take a graphic form, in which she swoops across the pages alongside her friends and contemporaries Modigliani, Picasso, Matisse, Duchamp and Hemingway.

The story of Prin could be told as a grim and cautionary tale – born illegitimate in Châtillon-sur-Seine in 1901, she died in equal poverty in 1953, after a lifetime of drink and drugs and debauchery. But this ribald comic strip version is as tender as it is witty, and is a complex portrait of the model and muse. The author and artist, Jose-Luis Bocquet and Catel Muller – whose collaboration has already won several awards for the original French edition – resist the temptation to turn Kiki into either an emblematic victim of male objectification or the proud symbol of female emancipation. Instead, Kiki's contradictions emerge from the cartoons: her liberated sexual freedom is shadowed by a masochistic tendency to forgive abusive lovers; while her joyous embrace of the pleasures of life (food, art, wine, song, sunshine) is enmeshed with drug addiction and alcoholism.

When Kiki's own memoirs were published in 1929 (and promptly banned in the United States), her friend Ernest Hemingway wrote an introduction that acknowledged her capacity for self-invention. "Having a fine face to start with she made of it a work of art . . . she certainly dominated that era of Montparnasse more than Queen Victoria ever dominated the Victorian era." Kiki's creativity was also apparent in the illustrations she sketched for her memoir, black and white drawings that shade between childlike innocence and something darker; and despite their surface naivety, her status as an artist, as well as a model, had already been consolidated with a sold-out exhibition of paintings in Paris in 1927.

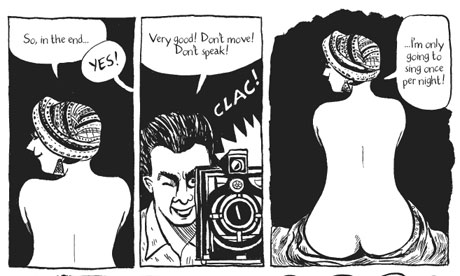

Nevertheless, the most enduringly famous image of Kiki is Man Ray's Le Violon d'Ingres, a photograph of her naked from behind, her signature bobbed hair hidden in a turban, her remarkable face almost hidden, and her voluptuous body transformed into a musical instrument by the addition of the "f-holes" of a violin. The title suggests Man Ray's inspiration came from paintings by Ingres; and also, perhaps, that he fingered Kiki as a plaything, just as Ingres played the violin.

Muller and Bocquet's cover is something of an uncovering for Kiki: for although the drawing is a reflection of Man Ray's portrait, this version has her head free of the turban, and her profile clearer than the original. You can see her charismatic features – big nose and playful eyes framed by the black sharpness of her hair – as a beguiling invitation to look inside. The pages that follow are filled with legendary men, the surrealists and cubists and dadaists who shaped bohemian Paris, all of them presented here fighting and eating and jostling to make a living, as well as making love, just like Kiki herself. But she is centre stage, the queen of Montparnasse, whether posing for Man Ray, or as a bawdy nightclub act, lifting her skirts and showing her bottom whenever the mood took her. (After a fashionable dinner given by Coco Chanel in June 1929, one of the guests, Maurice Sachs, noted in his diary that "Kiki, who had too much to drink, sang very obscene songs.")

In the end, she was too much for Man Ray to handle; not least when the instrument of his art and pleasure was noisily arrested, after she got into a fight in a Nice bar and hit the policeman who called her a whore. Man Ray employed a lawyer to represent Kiki, who could only get her out of prison by declaring that she had a "nervous disorder"; thereafter the relationship between artist and model was sporadic, and ended when Man Ray fell in love with his protégée, Lee Miller, in 1929, by which point Kiki was already involved in another affair.

Kiki's career subsequently veered between cabaret and drug addiction, and by the time Man Ray returned to Paris in the spring of 1951 (having left the city at the outbreak of the second world war), she was swollen with alcoholism and dropsy. Man Ray offered help, to which she gave her renowned reply: "No! A raw onion, a heel of bread and some red wine is enough for me", and after he pressed money on her, she promptly handed it over to a beggar. That, at least, is the comic-strip version, but it has the ring of truth, as does the last page of the story, in which Man Ray weeps when he hears that Kiki is dead at the age of 51, the artist alone in his studio, but surrounded by the artworks he had made of the woman who finally slipped out of his grasp.

Justine Picardie's Coco Chanel: The Legend and the Life is published by HarperCollins.