"I pray that [this book] becomes a kind of Holy Writ for notation in this coming century. Certainly nobody could have done it better, and it will be a reference for musicians for decades to come." Not my words, but those of Simon Rattle (one of only two conductors to escape censure from Peter Maxwell Davies earlier this week; only Rattle and Pierre Boulez emerged unscathed as "masters of their art" in his recent pop at the profession) on Elaine Gould's new book, Behind Bars: The Definitive Guide to Music Notation.

This "wonderful monster volume" – Rattle again – is indeed more than the sum of its parts. Gould's book is the result of decades of experience as senior new music editor at Faber Music, where she has worked closely with composers like Jonathan Harvey, Oliver Knussen, Colin Matthews, and Thomas Adès, and what she has to say in Behind Bars transcends the book's first appearance as a manual of notational best practice. Under the surface of its guide to producing the best and clearest scores – the arcana of making sure you're not asking your harpist for too many pedal changes, that you change clefs in the right place in your orchestral parts, and how best to indicate the plethora of extended instrumental techniques in so much contemporary music – this book expounds an alchemical formula for musical communication. Gould's book shows composers how to ensure that the magical transfer of musical ideas from their imaginations to their scores, from their performers to their audiences, is as seamless as possible. Behind Bars is a practical revelation of the poetics of musical communication.

It's especially necessary in the early 21st century. You might think that after centuries of ever-more sophisticated copying, printing, and digitising of music notation that all the problems had been solved. Not a bit of it. The rash of computer scores produced with programmes like Sibelius in the last couple of decades are a mixed blessing. Software like Sibelius allows composers to create full scores and individual parts for the musicians at the click of a button, yet it's too easy to overlook the kind of problems that Gould talks about – where a badly placed page-turn in your string parts can mean the difference between a good performance and a catastrophic one. Gould quotes Mahler's frustration with the copyist who mauled the material of his Eighth Symphony before its first performance in Munich in 1910; looking at his exemplary manuscript of the Fifth Symphony that the Morgan Library has just made available for free online, you can see that Mahler abided by Gould's principles of clarity and consistency.

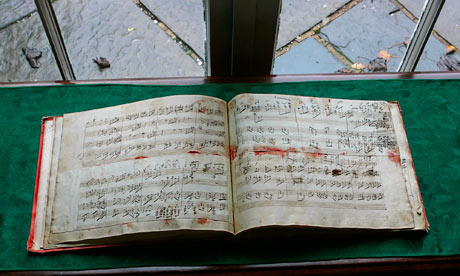

But I wonder what Gould would say to Beethoven, if she were faced with pages like this, from the manuscript of the Ninth Symphony, whose facsimile was recently published by Bärenreiter? It's not just a contemporary phenomenon: composers have always pushed at the limits of musical and notational comprehensibility.