One hundred and fifty years after his birth, Chekhov's plays have become almost as much part of the British theatre's repertoire as Shakespeare. What also intrigues me is the way writers are drawn to him as well, and not just as translators.

There's a Trinidadian Three Sisters, a Liverpudlian Three Sisters, a Seagull and a Cherry Orchard in the Hamptons. Uncle Vanya has visited North Wales and Australia, and in Drowning Crow, The Seagull plays out in the black artistic community of South Carolina, in which Arkadina is a doyenne of the Negro Ensemble Company and Konstantin Treplev the performance poet C-Trip.

Other writers have given us glimpses of lives around the plays; Helen Cooper's portrait of the unhappy Mrs Vershinin, or Brian Friel, whose Afterplay imagines the meeting of Sonya from Uncle Vanya and Andrey from Three Sisters. Reza de Wet's Three Sisters Two and Nic Ularu's The Cherry Orchard Sequel place Chekhov's characters in the tumult of the 1917 revolution. Other plays have wondered how Arkadina reacted to her son's suicide and how the sisters would actually fare if they ever got to Moscow.

Howard Barker's (Uncle) Vanya deconstructively pits Chekhov against his own characters and Chekhov Lizardbrain quirkily mixed Three Sisters with a thesis on neuroscience. Lines from Three Sisters illuminate the moral darkness of Mark Ravenhill's Shopping and Fucking. Ben Greenman of the New Yorker has mixed Chekhov's short stories with the contemporary world in a volume called Celebrity Chekhov ("now with famous people!" promises the cover).

You can trace pretty much the whole of Chekhov's adult life by watching La Steppe, Subject for a Short Story, I – Actress, Chekhov and Maria, and Your Hand in Mine. In The Woman Who Wouldn't by Gene Wilder (yes, that Gene Wilder), the hero is sent to a spa in Germany where he meets a dying Chekhov. Raymond Carver's Errand retells the story of Chekhov's final minutes with characteristic impact and precision.

My own play, Chekhov in Hell (about to open at the Drum Theatre, Plymouth), takes the story even further: the first scene gives us the death of Chekhov; in the second, he is startled to wake from a 100-year coma and takes a bewildered tour of contemporary Britain, from lapdancing to reality TV, feng shui to Twitter.

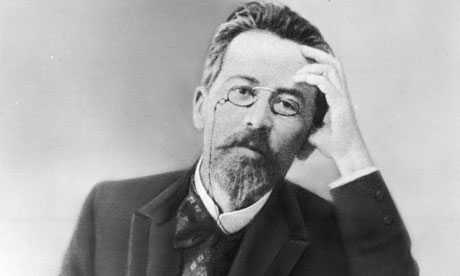

What hubristic impulse is it that draws us to rewrite this man and his work? On one level it's obvious. He's a great writer and his characters live in the imagination. His short theatre career has encouraged many to supply the plays he didn't live to write. His images – the dead bird, the failed shootings, the country estates, the axes hitting the trees – have all insinuated themselves into works as diverse as Ibsen's The Wild Duck and Louis Malle's Milou en Mai. And he's iconic, too: the pince-nez and neat goatee are almost as recognisable as the starched ruff and high forehead of Shakespeare.

But also, I think, Chekhov is a mystery. There are some playwrights who are so busily present in their work that it's like you have the author beside you murmuring comments on the action. Chekhov is different; what does he think of his characters? Does he admire them or pity them? Ask us to examine or ridicule? It's never obvious. Chekhov's characters tend to let their mouths run away with them (Gayev in The Cherry Orchard fills a silence with an idiotic hymn of praise to a bookcase that, even as he's saying it, he must regret). It's almost as if Chekhov lets silences form in his play, which his characters nervously fill and thus reveal themselves.

For me, this is why Chekhov continues to be an important model. We've turned away somewhat from "messages" and "thesis plays"; the contemporary preference is for authorial blankness, not of style but of commentary; we like stark juxtapositions and moral emptiness, the responsibility placed on the audience to make the judgment. Chekhov is rightly admired for the complexity of his characters and the extraordinary elegance of his narratives, but beneath that it's the dark, dark irony and pitiless gaze that make him truly our contemporary.