Superficially, Brooklyn is a book in which very little happens. Don't, as I almost did, let that put you off.

It tells simply of the move a young Irishwoman – Eilis Lacey – makes from Wexford to New York City in the 1950s, of her generally happy relationship there with an Italian American called Tony, and of a trip she takes back to Ireland to attend a funeral. Tóibín himself is said to have described the book as "quite low key, about somebody very ordinary" and the details he attends to are everyday, even banal. We learn about Eilis's work in a shop in Ireland, then another in Brooklyn, together with a course in bookkeeping she takes to advance her career. When she isn't at this dull and routine work, we generally see Eilis at home. First she spends a lot of time at the kitchen table in a small nondescript house in Ireland with her taciturn mother and older sister. Then she's in a boarding house where gossip is frowned upon and the landlady insists that most conversations revolve around fashion. Pretty much the most exciting thing Eilis does is to attend dances organised by the local clergyman and even those she tends to leave early. This is not War And Peace. It isn't even peace …

Which goes to explain why Brooklyn initially caused me some confusion. There's a certain beauty to Toibin's prose. Nothing demonstrative, just a general lean cleanness. There's also a good streak of sly humour – the kind you laugh about half a page after you've read it. ("Now there are people who come here on a Sunday, if you don't mind, looking for things they should get during the week. What can you do?" asks Miss Kelly, the owner of the only shop in Eilis's neighbourhood that opens on a Sunday.) Yet breaking away from the novel, I sometimes wondered why on earth he was telling me about this unremarkable woman's unremarkable life. Sure, he's done a fine job of bringing the characters to life and giving them a real-seeming world in which to move around – but to what end?

An answer of sorts began to dawn on me as I became increasingly wrapped up and read more attentively. Tóibín's gift is to demonstrate how extraordinary the mundane can be – or at least, how special an individual life is to the individual who is living it. Eilis's family, career and relationship in post-war America might seem insignificant when viewed through the reverse telescope of history, but to her and those around her, they were everything.

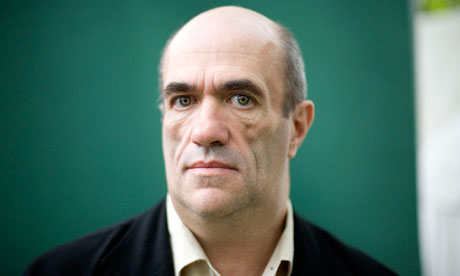

Gradually, that little everything started to feel significant to me, too. Tóibín's warm, good-humoured portrayal of Eilis was thoroughly endearing – but it was the sense of deeper knowledge that had the greatest binding power. As Liesl Schillinger said in a review of Brooklyn in the New York Times, "Colm Tóibín … is an expert, patient fisherman of submerged emotions." Most of Tóibín's characters shun demonstrative outbursts – or even discussions of their feelings. "They could do everything," he says of Eilis and her family, "except say out loud what it was they were thinking." Nevertheless, with a few deft hesitations, telling procrastinations, and indications of words left unsaid he makes it feel as if we are looking onto their souls.

I became so involved that the final part of the novel made for unbearably tense reading. Again the exterior focus is on superficial matters: a few trips to the beach, a wedding, a few awkward social encounters. But the interior question that Eilis must face – whether or not to return to Brooklyn – becomes all-involving. It was here I really began to understand Tóibín's skill. When he wrote that Eilis was trembling, I just about trembled too. I was his.

Maybe there's a criticism in that this final part comes and goes in an overwhelming rush. Perhaps the book was too front-loaded, with so much of its drama coming only at the end. But then again, perhaps this brief storm after so much calm is true to life. The fact that Eilis doesn't always live at a high pitch is just another of the things that make her seem so real. It should also only really be taken as a compliment to the book that one reaches the end hungry for more. It is (with apologies to Jane Austen) a delightful read – perfect in being much too short.

I liked it anyway. But do you? Are you with Rick Gekoski in finding it "shocking" that Brooklyn didn't make the 2009 Booker shortlist? Were you pleased that it did receive recognition in the Costa? Or do you feel like the great John Self that it "lacks oomph". Over to you.

Comments will be most appreciated, as they'll help inform John Mullan's final book club column this month.