A few weeks ago, I was reading Mary Renault's Fire From Heaven (one of the nominees for the Lost Booker prize) and admiring the way she managed to deal with the issue of there being so few contemporary sources about Alexander the Great – but so many legends. With fine synchronicity, pretty much the day I blogged on the subject, another book tackling a very similar problem arrived in the post.

This time the book – Carthage Must Be Destroyed, by Richard Miles (by whom – full disclosure – I was once lucky enough to be taught by when at university) is a serious narrative history rather than an epic novel, but reading it is no less exhilarating. It describes the rise and fall of Carthage and its most famous son, Hannibal. Even if most of the pieces weren't missing, this would be a gnarly puzzle thanks to the fiendish complexity of Carthaginian politics (not to mention that nation's propensity to call everyone either Hanno, Hamilcar or Hannibal, which makes the book's index an amusing read).

As it is, though, the issue isn't just how to write about a nation distant in time, place, and culture, but how to write about a civilisation that was wiped off the face of the earth more than 2,000 years ago. Carthage was levelled and burned in 146BC, its population slaughtered or sold into slavery and its language, culture and literature all but annihilated. "At times researching a history of the city is like reading a transcript of a conversation in which one participant's contribution has been deleted," says Miles. What's more, the side of the conversation that remains was generally written by the very Romans who did the deleting – so has to be taken with hefty pinches of salt.

In spite of all the obstacles, however, Miles paints a full and convincing picture of this lost civilisation and its players. It is at once a society to which we can easily relate, and one that feels very alien. The Carthaginians were governed by corrupt elites prone to ill-advised overseas ventures, for example, but also overseen by strange gods with a penchant for the blood of human children.

Rising out of this intriguing mishmash is Hannibal. His story is well-known, but it doesn't suffer any in the retelling. Miles has a healthy historian's scepticism for some of the more outlandish claims that have been made about him (he doesn't, for instance, buy the idea that Hannibal managed to persuade his elephants to cross a river using their trunks as periscopes), but he still creates an impression of near superhuman ability.

Next to his tactical achievements and his ability to outwit the Romans, crossing the Alps with elephants while fighting off Gallic raiders starts to seem like minor achievements – although no less interesting for that. (On that note, I'd also strongly recommend listening to Patrick Hunt's Stanford lectures on the crossing – especially John Hoyte's account of his 1950s recreation of the feat – complete with an elephant called Jumbo.)

But it isn't all derring-do. One of the most powerful aspects of the book is the feeling it creates for the brutality of ancient life. Alongside those sacrifices and the murderous intrigues of the Carthaginian court are numerous breathtaking stories about the hardship of ancient warfare. There was huge risk involved in marching such vast distances, let alone in battle (especially given the threat of cholera for anyone unlucky enough to drink water at the rear of the baggage train).

The figures, meanwhile, can be staggering. At Cannae, the best estimate is that Hannibal's army killed 70,000 Romans – a death toll similar to that of the first day of the Battle of the Somme. The comparison becomes all the more striking when we remember that the victims were cut down by hand, rather than by machine-gun fire. Hannibal's death, too, was hard and cruel. His last great defeat came at sea, near Pamphylia in Asia Minor, where Carthaginian ships fought with the Romans against him (as Miles says "we can only imagine his shock and sorrow".) After that he travelled from court to court – less than an exile, since his homeland was no more. Pitiful and powerless as he was, the Romans still hunted him down to Bithynia, where they were only denied revenge by his decision to take poison.

The irony, though, is that the more the Romans tried to destroy Hannibal's legend, the more it grew. How many non-classicists, I wonder, know the name of the man who finally crushed Hannibal, or where that battle took place? Yet everyone knows Hannibal crossed the Alps with elephants. Carthage has lived on in art, too, from Virgil's Aeneid to Flaubert's Salammbô (a "rollercoaster ride of sexual sadism, extreme cruelty and repugnant luxury" according to Miles) to a Hollywood film of its final days currently in production.

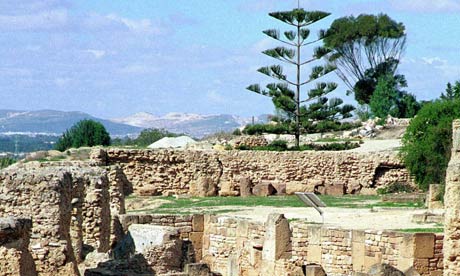

The physical destruction of the city helped cement its place in history: Miles is at his most evocative when he talks about the scant remains the Romans left. One illustration he gives of how bad things got for the city's inhabitants during the final siege is that rubbish collection ceased. "A resident's nightmare, but an archaeologist's dream," says Miles. During the last few years (years!) bodies were the only waste to be removed, while in the last "terrible months of the city's existence, in contrast to the care that had traditionally been taken of the dead, the corpses of both rich and poor were unceremoniously dumped in mass graves".

More than the pyramids, more even than the Colosseum and the Aztec temples, the flattened outlines of this once-great city remind us of the idea first put about by Herodotus: that history is all about rise and fall – and far more fall than rise, in the long run. There can be few better lessons in mortality and mutability than those sad ruins – or than this excellent book.