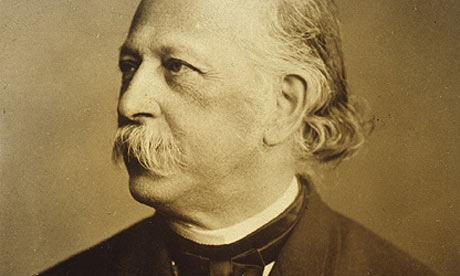

Theodor Fontane is not the sort of novelist whose works I feel moved to press on other people. I'm not sure why. He has been described as a "loveable" writer, but I'm never confident that the rather chilly charms of Effi Briest and Frau Jenny Treibel will be apparent to others. Nevertheless, I've always been drawn to the Prussian wanderer, and particularly to his travails in the rough and tumble of the German publishing industry in the late 19th century.

Fontane was writing at the time of the emergence of a mass market for fiction, in which the origins of today's publishing industry can be easily discerned, most notably in the privileging of profit over aesthetic concerns. Improved printing technology meant books and journals could be produced with increased ease. (This did not impress Fontane, who called modern editions "cheap and nasty".) Literacy rates were increasing, yet regard for high-quality literature was wavering; the Stiehl regulations of 1854 actually greatly reduced classical literary education in schools. More than ever before, the function of literature veered towards entertainment and escapism. For writers with ambitions in the Goethe and Schiller direction, this was a discouraging situation.

As books remained beyond the means of most of the reading public, the "family journals", with their massive circulation, were easily the best sources of income for fiction writers. Many of Fontane's novels were serialised in publications such as Die Gartenlaube, which rose to prominence by ruthlessly slashing its subscription prices to undercut rivals. Unfortunately, the journals also acted as a literary straightjacket. The emphasis was on tried-and-tested formulae and genres; guidelines were issued to writers that included an insistence on happy endings. In a crowded market, editors were loath to take risks lest they alienate readers. For Fontane, the choice for writers was stark: either maintain artistic integrity and starve, or compromise your literary ideals for money. "The ink slave is born," he noted wearily in 1891.

Fontane's particular ire was reserved for those he saw as the true culprits: the readers. "The taste and voice of the public are being more anxiously obeyed than is necessary," he wrote in 1881. He considered this a poor editorial strategy because this new audience had no taste at all: "I can't write robber stories and adventure nonsense to please the mob," he complained to his wife. His was not an original sentiment; Gottfried Keller wrote in 1843 that he wished to burn down all libraries and "force people to read either something good or nothing at all". Neither Keller nor Fontane appears to have considered the possibility that reading habits were shaped by the output of the journals, rather than the other way round. It can't have helped Fontane's attitude to his audience that his attempts to move beyond the constraints of popular taste were met with hostility. In response to Fontane's increasingly racy themes, one reader ("Outraged of Bavaria"?) spluttered to the editor, "Will the disgusting whore-stories never end?"

Not only did those pesky readers persist in buying trivial rubbish, they also failed to show sufficient respect for writers. The mass distribution of literature had led to the demystification of the author and the assumption that "everyone can write," as Fontane asserted gloomily in an essay on the social position of the writer. Even the cultural elite were culpable. Fontane lamented the fact that those who appreciated good writing were only interested in the classics: "Their attitude to modern writers is often not merely indifferent, but actually hostile." He criticised the herd mentality of supposedly cultured readers, claiming that nine out of 10 of his acquaintances had not bothered to read his latest novel, while "the 10th reads it, falls silent and withholds his judgement until 'the critics' have spoken."

Fontane's later disdain contrasts with his youthful enthusiasm: just after his first novel, Before the Storm, appeared, he insisted: "I am understood by all my readers, even the half-educated." His later outbursts seem to be the despairing conclusions of a writer worn down by the demands of trying to work within a mass market framework to produce fine art. Yet for all his complaints, Fontane made considerable progress as a writer, moving from his mawkish first novella, Sibling Love, to the subtleties of Effi Briest and the intellectual heights of Graf Petöfy, which contains 70 references to 30 different writers. There's something inspiring about his drive for quality: "Cécile is more than an everyday story," he wrote to a critic in 1887. "At least, the story wants to be more than that." And indeed it is, despite displaying many of the love story conventions of the time.

Fontane's situation may therefore be a comfort to writers wondering where their work fits in with the morass of Dan-Brown-alikes and celebrity memoirs today: the mass market can act less as a straightjacket and more as a spur to greatness.