I was talking to the journalist Lindsay Johns the other day when a look of pain came across his face. "Have you come across this street slang Julius Caesar?" he asked. I gritted my teeth. "No, but I can imagine," I replied.

Lindsay mentors kids in Peckham and is sick to his back teeth of what he calls the "rush to relevance"; that is, the idea that if someone comes from "the street", the only way Shakespeare could have anything to say to them is to make the works relevant to their supposedly jive-talking, hoodie-wearing, knife-packing lives. The fact that Lindsay has enthralled kids with Latin in deepest Peckham gives lie to such nonsense. And as our conversation progressed I realised I was also sick to the back teeth of something else: the misuse, and downright misunderstanding, of slang in literature by arts policy types.

Don't get me wrong. It's not slang per se that is the problem. One argument against such out-of-hand dismissal of the colloquial is Shakespeare himself, who spiced his poetry with the modern, using words and phrases that chimed with the groundlings as much as with Elizabethan courtiers. Indeed scholarly fascination with Shakespeare's slang is longstanding. In many respects, dialect and idiom are the warp and weft of English literature, whether it be Coleridge's and Wordsworth's Lyrical Ballads or Thomas Hardy's Wessex chronicles. It could be argued that English literature sprang from idiom, with the very first stirrings of vernacular verse in Old English.

But there is a difference between idiom and modern slang in literature. Shakespeare's use of slang opened up the world of the theatre to all of the audience, displaying the mental agonies of the Prince of Denmark to the most boisterous groundling and bringing the horseplay of Dogberry and co to the attention of the most cerebral courtier. Modern slang is different, being cut through with dark knowing humour and packing a linguistic punch, as the Guardian's recent compilation of 1950s slang bears witness.

Twentieth-century slang is often self-consciously a code, concocted by a clique – and the use of slang in modern literature is generally not to include but to exclude. On The Road really was about the in-crowd and whether or not you were of the generation that could "dig" the lingo. Such use of slang in literature is urban, knowing and modern, cocking a snook at some readers, while winking at others.

But not every Joe from the street corner can make slang work in this way. Firstly, it has to be authentic and thoroughgoing: you can't glean slang from snatches. Secondly, it has to be handled by a literary master. Slang turns the challenge of literature on its head: it is no longer high-minded literary language holding a door open to an imaginary world but the coded vernacular of slang that teasingly slams that door in our face. The reader has to give something over to this linguistic world, immerse herself in another familiar but alien language. Something shifts in the literary hierarchy. The infusion of Holden Caulfield's off-the-cuff colloquialism through the narrative fabric of The Catcher in The Rye is not simply an aspect of Salinger's central character but the very heartbeat of the narrative world he has imagined. Irvine Welsh's virtuoso passages of Glaswegian slang in Trainspotting are at once rebarbative (deliberately repelling the cultured ear of middle class readers) and the means by which readers submerge themselves in the world of Leith.

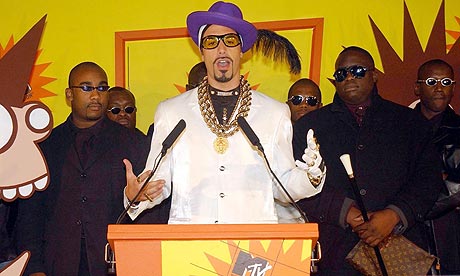

This is what drives me nuts about the "Let's do Shakespeare in slang" school of thought. Not only is it patronising to those it hopes to welcome, but it entirely misses the literary purpose and value of slang, usually utilising the lamest, least challenging has-been manifestations of "cutting-edge, fresh-from-the-street" talk. Take a line from the street slang Julius Caesar: "I come to bury Caesar, not big him up." Are you kidding me? Even to an old fogey such as myself, this sounds dated. When well-meaning literary professionals seek to get down with the kids in this way, the world really is turned upside down. On one side, those who should know better abdicate their duty to introduce the next generation – wherever they come from – to the very best of literature; on the other, you have a misplaced scramble to latch on to and leech off the knowing cool of youth. It's quite possible that the next great work of literature will emerge from that knowing cool. It's certain, however, that it won't come out of any arts project that makes the relevancy of slang its raison d'être.

My advice to anyone engaged in such "relevant" activity is to please stop stalking the kids. To be old-fashioned about it, it simply is unseemly.