It's lonely being a fan. It can feel a little like being Cassandra, the ancient prophet heeded by no one. For the past 10 years, since her death in February 1999, I have felt this way about the writer Iris Murdoch, author of The Black Prince, A Word Child and The Philosopher's Pupil; don, Dame, winner of the Booker, the Whitbread, the James Tait Black Memorial prize and countless others, author of 26 astute, exciting, intelligent novels that attained the almost unheard-of feat of receiving meaningful critical acclaim alongside hit-level sales.

It's time Murdoch was recognised as one of the greats. Her death from Alzheimer's coincided, more or less, with Richard Eyre's emotional film Iris. The film was inspired by the graphic, despairing memoirs of Murdoch's husband, John Bayley, who wrote about his years caring for her in a state of mutual squalor and bafflement. Iris was a personal film for Eyre, whose own mother died of Alzheimer's. I do not for a moment think he was participating consciously in that sadly standard hobby of belittling and objectifying a female artist, passing over her cultural achievements to focus on her bodily lusts (played out by Kate Winslet) and then her bodily and mental decay (played by Judi Dench).

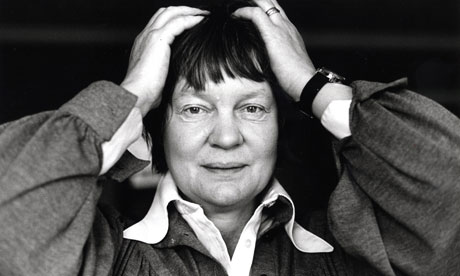

But still, it is unfortunate. Murdoch was a genius. She wrote with such depth and variety, producing nearly a book every 18 months over four decades, that it is hard to summarise her achievements in this brief column. She took on the most profound moral questions that we ordinary, flawed, troubled creatures grapple with: the battle between good and evil within ourselves and within society; the possibility of faith and the death of God; the occasionally delightful and playful, occasionally dangerous and destructive urges of erotic desire; the compulsions of amorous and intellectual obsession; artistic creativity and the artist's ambition to create the one ultimate and universal work that addresses every moral dilemma with its overarching theory.

All that makes it sounds as though reading her work is like finding oneself in the middle of an endless Brothers Karamazov-like rumination. Yet lightly thrown over these huge issues were plots of a disarming playfulness, creativity and joy: realistically daft adults making buffoons of themselves, androgynous girls, tough but unimaginative women, happy dogs, tortured gay priests, angry clever bullies and power-holders, hypocritical husbands, melancholy wives. Murdoch's characters are fallen, her world post-lapsarian, full of contingency and realistic illogic. Her characters act against their own happiness with frustrating frequency. But then, that is what people are like. They behave absurdly, yet Murdoch does not write absurdly. She examines human silliness with her own clever, tolerantly smiling seriousness.

There is another aspect of her work that is difficult to touch upon. Somewhere between the plot and the themes and all those other staples of GCSE lit-crit terminology, one finds scenes of heart-freezing sublime and poignant beauty. Michael kissing Toby in The Bell. The charged discourse on Hamlet during a lesson in The Black Prince. And, strangest and most chilling of all, a vision experienced by Anne Cavidge, the ex-nun protagonist of Nuns and Soldiers: "Jesus Christ came to Anne Cavidge in a vision. The visitation began in a dream, but then gained a very undreamlike reality. And, later, Anne remembered it as one remembers real events, not as one remember dreams." Goosebumps are rising on my arms as I write this, because what follows is an utterly believable, authentic-feeling encounter with the son of God – and very nice he is, too.

In the course of making a radio documentary to coincide with the 10th anniversary of her death I spoke to Murdoch's friends and biographers Peter Conradi and AN Wilson, two candid stars of the piece. But the most happy-making encounter was at Kingston university, which houses Murdoch's archives. It was no surprise to survey the books she herself looked to for power, and find most of the philosophical masterworks of western civilisation (and an intriguing array of works on eastern mysticism) carefully shelved, far outnumbering any novels. What did surprise me was something the director of the archives and Murdoch expert Dr Anne Rowe told me, about the new generation of young students who read Murdoch for the first time and say with awe that the excitement, insight, beauty and depth of it has changed their lives.