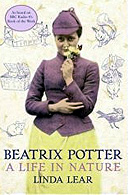

Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature

by Linda Lear

Penguin £25, pp554

One hundred years after The Tale of Peter Rabbit was the word-of-mouth sensation of Edwardian publishing, its author's tale is again making headlines. The story of the exacting, upper-middle-class spinster from Kensington and her reluctant acquisition by the Bloomsbury firm of F Warne & Co became book-trade folklore many years ago. Now, Miss Potter's awkward love affair with Norman Warne, her editor, has also passed into widescreen mythology, starring Renee Zellweger.

The Beatrix Potter story was always a good deal more complicated than a romantic movie. Those exquisite little books with their Tiggywinkles and Puddleducks were published into a booming domestic market for young readers of all classes, liberated by the 1870 Education Act. In hindsight, Potter was joining Kenneth Grahame ( The Wind in the Willows ), JM Barrie ( Peter Pan ) and even E Nesbit ( The Railway Children ), a disparate group of writers for children whose stories answered an insatiable English appetite for pastoral fantasy. Much later, this would be satisfied by Tolkien's tales of the Shire.

Since her death in 1943, Beatrix Potter has been the subject of, first, Margaret Lane's The Tale of Beatrix Potter (1946, revised 1985), then Judy Taylor's devoted biographical scholarship and, finally, a bunch of inferior American lives. But Miss Potter was a dumpy, practical and fanatically discreet body. Her life and opinions have proved a tough nut to crack. Even after Leslie Linder's publication, in 1966, of her secret diary, none of her worldwide fans was much the wiser. She has remained enigmatic, apparently beyond the reach of analysis. It was only a matter of time before someone placed the Potter miniature in a more ambitious frame. To elevate its subject beyond the mundane, domestic world from which Potter and her stories sprang, this new life casts its subject as Potter the preservationist.

The painting of a green Beatrix is Linda Lear's explicit intention and it makes for persuasive, if rather earnest, reading. For Lear, Potter is a naturalist manque first, a children's writer second. To amplify this portrait she focuses on Potter's teenage years, colouring a version that in its sketch form in previous lives was not treated with appropriate seriousness.

Lear's Potter is a solitary, misunderstood adolescent who, happy only in nature, roams the Lake District in search of fungi during the summer holidays of 1895 and 1896. Inspired by the prospect of professional mycology, she talks her way into the research side of Kew Gardens. Finally, in 1897, she presents a scientific paper to the Linnaean Society. Potter was listened to as a brilliant amateur, but as a single woman in late Victorian England there was no way forward in the world of spores. Frustrated, she turned to her 'bunny books'. Once she had made her fortune with Warne & Co, and been cruelly denied marriage to one of its partners, Potter retired to Hill Top Farm, Sawrey, Cumbria, and immersed herself in land preservation and rearing rare livestock. Eventually, she would be one of the great benefactors of the National Trust.

Towards the end of her life, we find her applying her knowledge of fungi to the public debate about penicillin. For Lear, Beatrix is 'clearly not surprised' by the discovery of the antibiotic properties of the penicillium mould. Why? Because 'she had discovered it herself many years before'. But that's not all. Potter the naturalist had reawakened an interest in regional ecology and her legacy is not just her famous grey Herdwick sheep, but an entirely new approach to the countryside.

This is a timely, and topical, corrective to the traditional tale of Beatrix Potter, but it misses the wood for the trees. Like so many late Victorian children, Potter's cold and lonely childhood is the real story. Her family were Unitarian, the wealthy beneficiaries of a fortune made in calico printing. In snooty Kensington, they were socially isolated. In response, like any outsiders, her mother and father were desperately anxious to do the right thing. Beatrix, the object of their status anxiety, could never live up to her parents' expectations for social advancement. Her father, Rupert, doted on her; her mother became 'the enemy'. Repressed at home, isolated in the world, young Miss Potter found companionship with pet rabbits and frogs whose lives she came to understand completely. She was an awkward young woman who found solace in drawing her animal companions.

The famous Tales began as illustrated letters to family friends' children. Publication brought a double release: she was rich and independent. She had also found love with Norman Warne. Tragically, he died of leukaemia shortly after proposing marriage. Bereaved at the age of 39, Beatrix Potter sublimated her grief in the Tales . Some of these, notably The Tale of Samuel Whiskers, are small masterpieces of nursery horror and Potter is one of English literature's most gifted storytellers, besides being a watercolourist of genius. You will find this version buried in Linda Lear's biography, but only once you have struggled past all the green stuff.