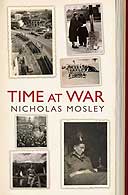

Time at War

by Nicholas Mosley

180pp, Orion, £14.99

Nicholas Mosley and I both have fathers who were top fascists in the 1930s. Oswald Mosley was The Leader (it always had upper case initials in fascist circles) and John Beckett was his propaganda director - Goebbels to Mosley's Hitler, if you like. They fell out ferociously in 1936, as only the leaders of fringe political groups can fall out, with a bitterness made all the greater because the stakes were so small (for fascism had failed in Britain by then). So I grew up hearing dreadful things about Mosley's father. I am sure, from the stiff and formal letter he wrote me refusing to be interviewed for my book about my father, that he grew up hearing the same sorts of things about mine.

But, being a postwar baby, I never had his remarkable experience of service in the British army while my father was in prison, considered by the government to be a potential traitor. This little book is the story of Mosley's war. It's attractively honest. There is no attempt to glorify the author, or to endow him with heroism, and when it describes events in which he displays considerable courage (he earned a Military Cross), it does so in a downbeat, self-mocking way.

But many people have written war memoirs, so this one can only justify itself by offering an insight into how Lieutenant Mosley squared the circle for himself, while his father, who had been close to Mussolini and Hitler and accepted money from them, languished in prison. And here the book is frustratingly uninformative. We do learn that when Mosley was on the verge of being captured, he realised he must avoid it at all costs: "Would it not look as though I were under the influence of my father?" Earlier in the book, he tells us that his father had secretly given him a code to mention if ever he were captured.

But mostly we learn what this 20-year-old Etonian aristocrat was thinking about God, and Truth, and Nietzsche, which is not particularly illuminating. And we get the authentic aroma of English snobbery in letters and extracts from his diary which, to his credit, he has reproduced as he wrote them at the time, with no attempt to massage away the awkward bits. At the officers' training camp "we split up into our school cliques - Etonians rather aloof and bored and hands in pockets: the rest alternating between Rugby raucosity and grammar-school timidity." These young men were to be placed in charge of grizzled professional soldiers, who became their sergeants and called them "sir" because they lacked the wealth and background that secured commissions.

Another remarkable illustration of snobbery comes in Mosley's account of his visit to his father and stepmother in Holloway prison. Sir Oswald and his wife, as aristocrats, were not expected to share the privations of their followers, who lived a spartan and unpleasant life in Brixton and Liverpool prisons, husbands and wives kept apart. The Mosleys were housed together in Holloway, and their son arrived with fine food and brandy which he was allowed to enjoy with them. The governor looked in, sat down, and accepted a glass, remarking: "You don't often find brandy like this these days."

There is one glaring lapse in the book's general honesty. Mosley approvingly quotes the military strategist General Fuller as attacking the conduct of the battle for Monte Cassino in 1943-44. He omits to tell his readers that this is JFC "Boney" Fuller, Oswald Mosley's leading supporter in the 30s, campaigner against war with Hitler right up to 1940, who after the war founded an extreme-right organisation with other boneheaded army officers and right honourables, saying that he foresaw "disaster after disaster for the world until it acknowledges that there are superior men and inferior men, and sees to it that the superior men are permitted to take their natural place in the world."

He is strongest, as befits an experienced novelist, on the colour and texture of war. Yet about the war itself, I think Mosley is understandably muddled. He is horrified that in 1945 he sees Cossacks returned to the Russians and to almost certain death, and at one point seems to be equating this crime with those of Hitler. More than once he appears to be about to question the morality of fighting Hitler, only to shy away from it. The shadow of his father hangs over this book and his life. There are only a few people who understand how dark it is, and I am one of them.

· Francis Beckett's book about his father, The Rebel Who Lost His Cause, is published by Allison & Busby