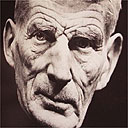

Although the Irish critic Vivian Mercier famously described it as a two-act play where "nothing happens ... twice", an Italian production of Waiting for Godot has been having a rather busier time off-stage.

Lawyers representing Samuel Beckett's estate, known for its iron grip on the playwright's works, objected to the use of female actors in the two main roles of Vladimir and Estragon, issuing an injunction against the theatre in Pontedera, Tuscany, to try to stop the performances.

The director and cast ignored the legal challenge, continuing the run of the play, and a court in Rome has now supported their position. It ruled this week that men did not have a monopoly on the roles, at least on this occasion. The theatre company's lawyer, Maurizio Fritelli, hailed the decision as a victory for civil liberties. "The sentence is valuable, not just from the technical point of view of the interpretation of the law," he said. "It reiterates that men and women have equal rights, given that it still seems necessary to point this out."

Lawyers for L'Agenzia Teatrale D'Arborio, which holds the rights to the Irish playwright's works in Italy, and the Society of French Authors, had claimed Beckett would have been unhappy about the use of women in his play about two tramps who wait in vain by a roadside for the arrival of Godot.

They said that, before his death in 1989, the Nobel Literature prizewinner had objected to previous attempts to use women in the production. They also cited a ruling in Paris in 1992, when a director was refused permission to use female leads after a judge said it was "violation of Beckett's moral rights".

The Pontedera theatre counter-claimed, saying that although sisters Luisa and Silvia Pasello were playing the parts, the characters remained totally male. There had been no attempt to alter Beckett's work, they said.

The actors, who have worked for the theatre company for years, and are near-identical twins and were brought in after two male actors who were originally cast pulled out of the production.

The theatre company showed the court a clause in its contract with the Beckett estate which said that if performers could not continue in the roles, it was permitted to change them. The clause does not mention the sex of the performers.

Director Robert Bacci said he was pleased the Pontedera theatre had won its case and called the legal challenge absurd. He said: "Silvia and Luisa look like men on stage and I chose them because they have played male roles before. We have used the text in its entirety and have in all other ways remained completely faithful to Beckett's work. We have followed his stage instructions down to the tiniest detail ... There is no element in the directing, acting, costumes or make-up that refers to a change in the characters."

He said he had invited Edward Beckett, the playwright's nephew, to see the production before deciding if it was acceptable, but he had refused.

Waiting for Godot is a comedy and was written in 1949. The play remains hugely popular and there have been many official productions as well as unauthorised versions where Godot actually arrives.

'A big enough classic to have own after-life'

It's an old battle: the freedom of the interpreter versus authorial prescription. And it's fascinating how many of these arguments focus on Beckett. In the case of Godot, there is certainly precedent for an all-female production: I know of at least one staged by Nora Connolly for Ireland's Taboo Theatre. Admittedly, Beckett scored the play for male voices but, as long as the rhythms of the text are scrupulously observed, where's the harm in a female version?

The play is a big enough classic to have achieved its own after-life.

Problems arise only when you start tinkering with Beckett's stage directions. In 1994 Deborah Warner and Fiona Shaw caused an almighty hoo-ha by fiddling with Beckett's Footfalls. The text insists that the confined heroine paces up and down a narrow strip of stage: Warner sent Shaw roaming all over the Garrick Theatre and the Beckett Estate prevented the production touring to Paris.

I could see their point: Beckett's later plays are like sculpted images and any deviation from the author's prescribed directions in effect de-natures them. But Godot is a different matter altogether. It is part of the universal language of theatre and has been played everywhere from America's San Quentin jail to Sarajevo after the bombing. If a group of Italian women now want to play it, it seems absurd to stop them.

Michael Billington