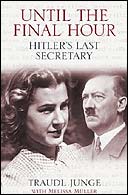

Until the Final Hour: Hitler's Last Secretary

by Traudl Junge; edited by Melissa Müller

Weidenfeld and Nicholson £12.99, pp261

Traudl Junge's first meeting with Hitler took place in 1942, in the middle of the night. She and the other girls who had applied to be one of his three secretaries were asleep in a train outside Führer HQ, East Prussia, when the call came. The dictator wanted to meet them; they should get up quickly and clean their teeth, for if there was one thing Hitler hated, it was the smell of cigarette smoke on a woman's breath.

'Panic broke out,' writes Junge in her memoir. 'Our curlers got tangled up, we couldn't find our shoes, our fingers were trembling so much that we could hardly do up our buttons.'

After a dictation test, Junge was told that the job was hers. Her response? 'I couldn't resist the temptation. I was 22, I had no idea of politics, I just thought it was wonderfully exciting to be offered such a special position.'

For the next three years, Junge lived with Hitler in his various bunkers. She walked with him, she talked with him, she listened to his lectures on the virtues of crispbread. During this time, she did not doubt - not even for a minute - that she was in the presence of a good and wise leader, though she was never a member of the party herself. Only when the sound of the Russian artillery grew so loud as to be almost deafening, did she begin to wonder. But still, she stayed with Hitler until the very end.

As Berlin fell and Hitler made it clear he planned to kill himself, she said her goodbyes and received two gifts for her trouble: poison from the boss, a silver fox fur from his new wife, Eva Braun. After their suicide, she went to their room. There, among the blood, she found a pink chiffon scarf, a revolver and a poison capsule. The latter, she noted, looked 'like an empty lipstick'.

Whatever else you think about Junge, she has a woman's eye for detail. Though her tale is extraordinary, she writes like a Dorothy Wordsworth of the Third Reich, conjuring up soft furnishings, frocks, supper dishes and crystal glasses with a kind of girlish delight. It's almost as an afterthought that she locates Hitler in the middle of this domesticity. The effect is startling, an especially hum-drum version of what Hannah Arendt called the banality of evil.

Only once does the evil itself break into the bunker. Over tea, a woman visitor brings up the deportations. 'My Führer, I saw a train full of Jews the other day,' she says. 'These poor people. I'm sure they are being very badly treated. Do you know about it? Do you allow it?' A painful silence follows. Hitler withdraws. 'Next day,' writes Junge, 'Frau von Schirach went back to Vienna. Apparently, she had exceeded her rights as a guest and failed to carry out her duty of entertaining Hitler.'

In Junge's story, which was written in 1947, though it was not published in Germany until shortly before her death in 2002, Hitler is presented as a pasty creature, charismatic but weedy. At the Berghof, his secretary is relieved to find that staff do not have to follow the same diet as their employer: 'I'd have had to be very ill to subsist on gruel, linseed mush, muesli and vegetable juice of my own free will.'

Fried eggs and creamed potatoes are his sole vices. At suppertime, he wastes no opportunity to put meat-eaters off their food by recounting tales of the abattoir. He is also eager to interfere in the lives of others. Matchmaking is one of his specialities, and he urges his little Traudl to marry an SS officer called Hans, though she would far rather have a long engagement. She mistakes this control freakery for paternal care. Most striking of all, given Braun's passion for fashion, is the dictator's attitude to clothes. 'When I think a dress is particularly pretty, then I'd like to see its owner wearing it all the time,' Hitler tells the ladies. 'She ought to have all her dresses made of the same material and to the same pattern.'

But as things grow ever darker for Germany, Junge's narrative takes on a new urgency. She is there when von Stauffenberg attempts to blow Hitler to pieces (after the bomb has gone off, it is all she can do not to laugh at the sight of her employer, his hair on end, his trousers hanging in strips from his belt like a grass skirt), and she is one of a handful of acolytes left in the Reich Chancellery when Hitler finally accepts that all is lost. The suppertime conversation now is of suicide, the cleanest ways to do it. 'When I remember how we all talked of nothing but the best way to die, I can't understand how it is that I'm still alive,' she writes. Why does she stay? She hardly seems to know herself. The last days have a sickly momentum.

She plays with the six Goebbels children, knowing that in their mother's handbag is the poison that will end their lives; she discusses the virtues of cyanide with Eva, who wants to be a beautiful corpse; and she attends a kitchenmaid's wedding. 'We congratulate the young couple and go back to the bunker of death. The newlyweds dance - on top of a volcano.'

Until the Final Hour is a remarkable historical document (and it comes with a good afterword by its editor, Melissa Müller, which describes Junge's miraculous escape from Berlin, her time in a Russian prison camp and, most poignantly, her old age: depressed, guilt-ridden, alone). But more than this, it is another painful reminder of how it is possible for a person - or even an entire nation - to sleepwalk slowly into sin. You put the book down and your skin prickles with the knowledge that, out in the world, there will always be invisible lines to be crossed. Mistakes: how easily they are made.

Traudl Junge, a girl from Munich who just happened to bear an uncanny resemblance to Eva Braun, wanted to be a ballerina. Picked out by the most mesmerising hand of them all, she ended up with an altogether different kind of career, and there are times when, as a reader, it's utterly hateful to find oneself so gleefully fascinated by it.